Born in Alabama in 1943, Jon L. Breen is a historian of crime literature. For example, his is The Fine Art of Murder: The Mystery Reader's Indispensable Companion, written with Ed Gorman, Martin H. Greenberg, Larry Segriff, as well as numerous novels and anthologies of short stories, especially Sherlockian apocryphals. He has also written parodies about Van Dine, Ellery Queen, Agatha Christie and John Dickson Carr. He won 2 Edgars, with biographical works: the first in 1982, with What About Murder? A Guide to Books about Mystery and Detective Fiction; the second in 1985, with Novel Verdicts: A Guide to Courtroom Fiction.

The parody we present is called The House of Shrill Whispers, and already from the title it denounces who is a parody.

Not only. The main protagonist, the detective who should solve the puzzle, is called Sir Gideon Merrimac, a private detective, whose name is a mix of Gideon Fell and Henry Merrivale, who has a tendency in the name and in the way of presenting himself of the protagonist, to refer to the typical bragging of Gascons. Not surprisingly, Merrimac will not solve the case.

Millard Carstairs is sitting in the train and looking at the legs of a beautiful young woman sitting in front of him. When he learns, after breaking the ice with the young woman, that she is Nancy Williston, of whom his friend Bill Clifton has told him, he is all happy. And then the girl, knowing it, tells him something: that is that uncle Margrove, who has four children including Bill and she who is an adopted daughter, has arranged for his assets to be divided between Bill and the girl, while the other three brothers, dissolute and greedy, Cavendish, Jessica and Franklyn, were excluded. Now she is afraid that one of the three wants to kill him; yet Uncle Margrove is not afraid that one of the three will murder him, but someone who seems to be able to enter a house with windows and doors locked from the inside, without leaving any traces. For this Bill called Millard, just as Milalrd would like old Giddy to handle that case, that is Gideon Merrimac, the greatest investigator in the world, not knowing that in turn Clifton Margrove, just Merrimac called to shed light on the case and save him. And in fact, a little while ago, on the train, in a bombastic and surreal way, wedged between two train carriages, Merrimac himself, who from how he is dressed and how he looks, looks like a photocopy of another Gideon much more known.

“..Who else was that fat and ruddy-cheeked? Who else wore two monocles, one in each eye, over a bulbous Fieldsian nose, a full set of gold teeth, and a pristine-white Colonel sanders goatee? Who else wore a black opera cape in the heat of July, over purple-and-gold-checked tree-sized trousers, from one of whose pockets protruded a flowered handkerchief into wich its proprietor periodically wheezed with earth-shattering volume, sometimes causing his cape to flutter and reveal a holstered antique dueling pistol hanging precariously onto his prodigious belly?”.

Just Merrimac claims to have been called by Clifton Margrove to solve the case of a seductive invisible killer who is ready to kill him. So Uncle Clifton not only barricaded himself in a cottage in the middle of the garden, but he had fake snow sprinkled all over the house, put 4 large floodlights that illuminate everything from dusk to dawn, and hired numerous agents. of Pinkerton to make the area even safer. Yet when Answorth, the 86-year-old butler, the only person Margrove admits to his presence, sees them to accompany them in the gig to the mansion, he informs them that their old uncle has been murdered. The fact is that the only footprints in the fake snow are those of the butler and no one else. Therefore it is logical to conclude that the murderer was either old Answorth (but what reason would he have?) Or the ghost of Admiral Wilburforce Cogsby, who visits The House of the Shrill Whispers in search of the spirit of his beloved, dead woman. July 11, 1870, the nights of July 12. I say nights because the admiral had created a family calendar in which July 11 was suppressed and there were instead two July 12s. And on one of the two consecutive nights of the 12th, the crime was committed, with an ancient pistol that has disappeared.

The Pinkerton agents can't explain how the killer got in, so much so that when Answorth went to his master, they erased the old man's footprints so that other footprints would be visible. Who was it of the 4 children who killed the father? Because a ghost goes through walls but doesn't hold a gun.

While Merrimac is elaborating a theory, Carstairs also gets to work. By questioning those present, he will find that the old butler had brought a baby elephant, that of the master, to his master, because he felt alone. But the elephant has disappeared from the cottage as well as the killer. Carstairs will find where the animal has ended up, will avoid a second murder and will nail the murderer, this time good-natured who in the end also renounces killing Carstairs as well as the butler and is ready to surrender himself to the police, knowing that there will be very few prisons in which he can stay.

The short story is one of the best parodies I've read about Carr (I also remember Brittain's, but Breen beats it). There is not only the tendency to make fun of the detective (and also Carr), but also to create a small story that would have all the characteristics and basic premises of a closed chamber, the craziest ever created, and then solve it with a bluff. , which in a certain sense disappoints the premises and expectations, but then looking back on it, not so much, because based on the data entered, it creates an adequate even if surreal solution.

The satire does not only make fun of the solution, but also something else: in fact, Breen enjoys mangling the names of Carrian characters. In addition to Sir Gideon Merrimac, who is the mix of the names of the two most famous characters of Carr, we find for example. the lawyer Butterick Parattler who immediately reminded me of another lawyer, present in two adventures of Gideon Fell, the lawyer Patrick Butler (Below Suspicion and Patrick Butler for the Defense) woman sitting in a train compartment (who then fall in love), and there is also The Constant Suicides which begins with a man and a woman sitting in a train compartment falling in love. There would also be a Carstairs that has a part in The Red Widow Murders, but oh well it may be a coincidence. Then there is the elephant, which is not really an elephant, or rather is a man in the costume of an elephant, walking on all fours, led from Answorth to Margrove Clifton.

Then there is the Locked Room, which would seem to be a quintessence of the closed rooms but in reality it is not, and precisely the characteristic that denies the Locked Room and which is that detail that Carr kept us that was never there in his novels, here there is. So… what kind of locked chamber is that? Exactly, just what you think. Which is also the reason for the motive, a surreal motive to say the least, at the basis of the murder of Sir Clifton Margrove.

And then there is finally another surreal if not grotesque scene: Millard Carstairs, investigating, ends up knocking down a shelf full of books in the servants' room, in the basement of the Villa dei Long Sospiri, and whoever finds buried by a mountain of old books? Answorth. The beauty is that the old books are old detective books by old authors, past and dated: Hume, Wells and Hanshew. As if to say that old Answorth had risked dying, overwhelmed not at least by valuable books, but by old junk, which hardly anyone read anymore.

So far we could talk about an excellent parody tale by Breen, surreal and also quite hilarious. However, what elevates this story and makes it a pearl, is another: it is the dialogue that at a certain point takes place between Sir Gideon, Nancy Wilston and Millard Carstairs. They are talking about the possibility that a lighter-than-air winged killer (so as not to leave footprints) passes through walls without leaving a trace. Nancy points out that no one has hypothesized that the killer is winged, Merrimac states that she should not rule out such a possibility and Millard explains to the girl that precisely this tendency not to discard any hypothesis is the secret of Sir Gideon's success.

“You ain’t just whistlin’ Dixie, honeychile,” old Giddy verified. “Old Giddy” Nancy probed “are you English or Southern American?” “Does it matter? After all, I’m just a character in a detective story and so are we all, so let’s get down to the problem at hand without further palaver.” “Look,”Millard objected, “you may be a character in a detective story, Old Giddy, but I’m real! Prick me and see if I don’t bleed.” “A character in a detective story had jolly well better bleed, son, or it won’t be much of a detective story. If were characters in a novel instead of characters in a short story, I’d discourse with you at appropriate length about the foolishness and absurdity of characters in fiction pretendin’ they’re real. It leads to characterization ad verisimilitude and other elements that stand in the way of a good story. But that is neither here nor there nor anywhere else”.

In other words, at

some point, this parody tale becomes fantastic. And the moment is precisely

this dialogue, which would have nothing to do with the story, which is detached

from the story that is being told, and which causes the bewilderment of the

reader and therefore also mine (Todorov states that because there is the

fantastic tale there must be the bewilderment, the amazement of the reader),

because in the moment in which Merrimac operates, which coincides with the

brief moment in which someone reads his story, he knows very well that he is a

work of fiction and does not pretend to be real. And this is a situation that

has never, ever been faced, since nornally in any story, not just a detective

story, each of the characters, in the context of the story in which it is

inserted, lives as if it were real; in other words, the characters live

according to the story. Never before has a character been seen, who in the

moment in which he lives he knows that he is not real. In a certain sense, this

situation is the opposite of what is sometimes seen in certain novels, for

example Nine Times Nine by Anthony Boucher, where we read Fell would have

been a real character used from Carr for his purposes, or the first novel by

Derek Smith, where read “Do you remember the Case of the Dead Magicians? A

spark of interest showed on the Inspector’s rugged face. “You mean that odd

affair in America, round about 1938? Yes, I remember. Homer Gavigan handled

that for the New York Police Department. Though I believe most of the credit

went to a man calling himself”-the Inspector’s voice held a high pitch of

unbelief-“the Great Merlini.”

“That’s it. Merlini solved the mystery, then wrote up the case as a novel,

calling it Death From a Top Hat. He collaborated with Ross Harte-they used

‘Clayton Rawson’ as a pseudonym.” Lawrence digressed slightly. ” There have

been four Rawson books to date, though only three have been published in

England. More’s the pity. Every one is first rate” (Derek Smith, Whistle

Up The Devil, chap. V pag.108).

A pearl by Jon L. Breen.

Pietro De Palma

P.S.

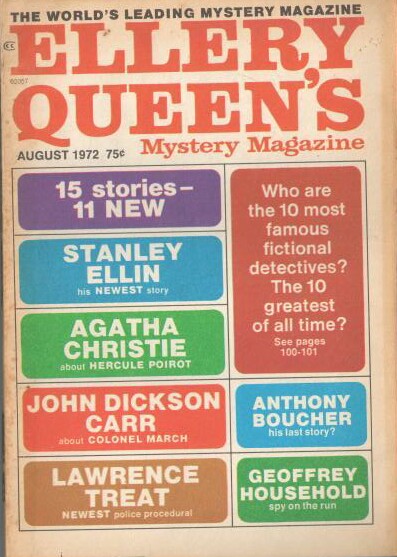

I publicly thank my great friend Luca Conti, editor of Jazz Music and already a great Italian translator of contemporary American harboiled, and the writer and editor Arthur Vidro, for helping me by giving me tips on how to find the original sources, very difficult to find unless you own EQMM of August 1972, or "Hair of the Sleuthhound" volume in which Breen inserted several of his stories including parodies, which Arthur told me about, and then Luca told me where to find it.

No comments:

Post a Comment