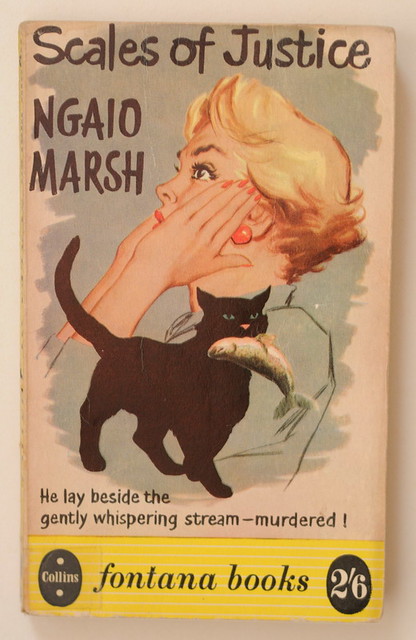

Scales of Justice by Ngaio Marsh is a novel of 1955, and is the eighteenth with Roderick Alleyn, the son of a lady, brother of a baronet, a nobleman who preferred the slow climb of a mistreated but great profession to a diplomatic career: that of the policeman. A noble policeman. There was another, "son" of another of the 4 Crime Queens, Dorothy Sayers: Lord Peter Whimsey. But that is a nobleman who improvises himself as a detective, partly out of snobbery and partly out of passion; here, on the other hand, we have a nobleman who has chosen, as a job, to be a policeman: starting from the ranks, as a simple Inspector. In this novel we find him Chief Inspector, followed like a shadow by his "help" Inspector Brer Fox.

The interesting note is that we find him operating in a fairytale landscape, in a corner of the old British feudal world, in which four families, the Cartarette, the Syce, the Lacklander and Danberry-Phinn, heirs of their traditional blazons for centuries, they are united, more or less firmly. The event that irremediably brings them into contact is the death of the old Sir Harold Lacklander, a very active and highly prestigious ambassador during the Second World War. Before dying he left the burdensome task of publishing his memoirs to his friend, Colonel Cartarette: burdensome above all because the theme of the death of the scion of one of the four noble families, the young Ludovic Danberry-Phinn, will certainly be addressed. he had worked with Sir Harold during the war, getting involved in a leak that had led the Nazis to win the English competition, that is of a hostile power, in the management of a certain affair of a neutral country: his suicide had followed . Now Sir Harold probably wanted posthumously to rehabilitate his memory. But how?

Everyone fears this extreme will of the old man. Mainly the close family of Sir Harold who fear the worst, that is to be directly involved and to pay the dishonor of the death of young Ludovic with the dishonor of someone else.

It is clear that they try to persuade the old Cartarette not to pronounce himself and not to publish the controversial seventh chapter; but the colonel is in one piece, and even if he is threatened with the breakup of the engagement between his daughter Rose and Mark Lacklander, the son of George Lacklander, Harold's eldest son and now a baronet, he does not break down and hold on.

However, he first wants to talk to Octavius Danberry-Phinn, Ludovic's father, who after the tragedy of his son lost himself, also losing his wife and living with a myriad of cats: he has a passion for trout fishing as well as Cartarette, and they often quarrel because the Lacklanders, essentially owners of Swevenings, a small town, have rented to their two friends the stretches of the Chyne, the river that flows through its meadows, whose waters are full of trout. The two are mainly adversaries, both wanting to catch “The Old Friend”, a trout of exceptional weight, over two kilos, which is the damnation of the fishermen.

In the late afternoon that the Colonel has to talk about the manuscript to Octavius, and then to Sir Harold's widow, and then go fishing, the unexpected happens: Nurse Kettle, who lives on the same property Danberry-Phin inhabits, skirting the Chyne near the spot where they go to fish for trout, near some weeping willows, finds the dead colonel, murdered.

After investigations and reconstructions, Alleyn will find the killer he killed for abject reasons and also wore clothes and shoes not his own to blame others. The last scene is one of love between Nurse Kettle and Captain Syce: the captain promises to her not to drink more whiskey and to be worthy of her love for her.

Meanwhile, let's say that among all the novels read by Marsh so far, this is a great masterpiece: I don't know if The absolute masterpiece, but certainly one of his best works. Ngaio, creates a large fresco of the English landed province, talking about four aristocratic families, with an extremely sophisticated writing, but which is very easy to read, and a psychological introspection that leaves little to chance, managing to wonderfully characterize each character. It is an extremely classic whodunnit, a very well-defined formal story, which is very, very much reminiscent of the typical British crime fiction novels of the 1930s and 1940s (in a sense it is an "out of time" novel, like if for Marsh there had not been the War, and the abandonment of the classic whodunnit, even if the Second World War enters the history of smear), set in rural villages, where the military, the reverend, the ladies of good society who participate in social events for charity, the baronet are always subjects who are the masters: in some ways this is Marsh's novel that is closest to those of Agatha Christie.

The novel is chock full of descriptions, and we know that descriptions are Nagio Marsh's trump card: when she describes a corner of paradise, you can be sure that sooner or later something dramatic will happen. Here even, it would seem that the bad omen is contained in a song, a very melancholy motif associated with a romantic vision: two young people united in an unequivocal gaze. The tune is “Come away, come away, death, And in sad cypress let me be laid. Fly away, fly away, breath; I am slain by a fair cruel maid. My shroud of white, stuck all with yew, O, prepare it! My part of death, no one so true Did share it” (from Twelfth Night by William Shakespeare). After all, the marriage between love and death is always present: in this novel it is particularly so. Where there is love or there would seem to be, there is always a wrong note: there is in the union between Kitty and Captain Syce in the past of the two, there is in the union of Kitty with George, of Syce with Kettle, of Kitty with Cartarette, by Mark and Rose.

I would also make a distinction regarding the sexual identity of the characters: male characters, austere, are always unlucky or cursed: Cartarette, a symbol of a past world, is murdered; Octavius is emotionally devastated by losing his son and wife; Syce is also emotionally devastated, having lost his beloved wife to one of his comrades in arms, and moreover he is semi alcoholic; Harold, remorseful of something from the past; George, lost in his extreme vanity, and in the empty defense of a noble prestige, is underestimated by everyone, even his mother. The female characters, on the other hand, are winners: Kettle is the nurse who always bets on something positive; Rose is a woman who would seem helpless because she is romantic but is instead strong in defending her love for her; Kitty is a strong femme fatale; and also very strong is Lady Lacklander, determined to defend her kingdom to the bitter end and the memory of her husband and her family, by all means. If we turn Brer Fox too, Alleyn's shadow is unfortunate, because he makes a half-idea about the nurse in the course of the novel, but then realizes that it is a vain hope. The only strong and successful male character is Alleryn. And some of her subordinates, for example. Sergeant Oliphant of the County Police. I I don't know if this difference between male and female characters, and the winning characterization of female ones, is ultimately due to the fact that Ngaio Marsh was a lesbian.

As always, Ngaio manages to direct a composite orchestra of characters, each with their own personality, managing to make everyone suspect something hidden, as well as what is being affirmed. And this is her extreme virtuosity: she has control of the macroform, which, for example, is lacking in many of her other British colleagues and especially in French novels. And so she invents an extremely complex plot, because it is the result of three subplots, which like three parallel waves with a sinusoid effect, continuously intertwine and interface, throwing the reader into complete amazement. Frankly, the trout thrown there raises the suspicion that fishing has little to do with the death of the colonel; and does the revelation of old Sir Harold's memoirs also come into reality with the crime? But if we get these two subplots out of the way, what are we left with? An investigation like many others, but in which the motives seem to be extremely limited if not absent. And then, here the two subplots return, and it is precisely some of their consequences that shed light on a solar but hidden motive, and to frame a truly despicable murderer: evil, envious, lustful, slothful, angry. It can be said that at least 5 of the 7 deadly sins are in his cords. That he kills, disguises himself to indict others, and gain a different advantage. Who despises other people's behavior, hiding a truly disarming emotional and spiritual misery.

What remains, until the end, is the suspicion that the same nurse Kettle and the same Captain Syce, who it is understood that they are cultivating an affair, are truly innocent and unrelated to the turbulence of events, or somehow they too become part of it. . The captain actually enters it, but in passing, only because his behavior has a decisive importance in the events that happen.

The structure of the novel is circular: in fact it begins where it ends. It begins with the nurse observing the curves of the hills, and the Chyne flowing between them, and the homes of the four ancient families of the place, and at the same time observing the map that she would like to complete, which would become like the one for visiting a certain tourist attraction; and it ends, with Captain Syce realizing what his nurse craved: a figured map.

It is the gift of an announced engagement, between two people each with his age and his history, each of which gives the other a little of his attention and his esteem: the captain does not take into account the social condition of the nurse, but look ahead; the nurse does not look at the condition of alcoholism as a form of depression, of the captain but she wants to see in him the ability to want to stop on the slope of the end, and instead of resuming the climb. This time with her by her side.

There is also in Marsh's novel, and it is very clear, a sort of revaluation of the small landed nobility, that social part that has held the intertwining of the basic values of society in its hands for centuries: it makes a mockery of them, but only to better define the forces of reaction, to make the best subjects spring the will to start over and in any case to give an example to those who are not of noble birth like them. One of the subjects that comes out best from the novel's weaving is the old Octavius: considered a half madman, upset by the death of his son and later of his wife, he vented his pain in love for cats and fishing. But even if he had, humanly speaking, to have a human resentment towards the Lacklander neighbors, he instead forgives, because he wanted his son, a candid soul, who did not betray, but was only negligent, and also when everyone should being against the Lacklanders, he holds out his hand. It is the old Lady, at the end of the novel, who, mindful of something that had broken one day, tightens hers to Octavius's, strengthening a bond, defrauded by betrayal and subsequently strengthened by the esteem and help of the vassal to her. man. It is a bit as if the lord recognized a vassal's merit and promoted him to social status.

And it is also how Ngaio Marsh, New Zealander forever, would affirm with conviction: God Save the Queen!

Masterpiece.

Pietro De Palma

No comments:

Post a Comment