WARNING: SPOILERS

THIS LONG REFLECTION SHOULD BE READ ONLY AFTER READING CARR'S NOVEL.

THEREFORE IT PRESUMES THAT YOU HAVE READ IT: in fact, the solutions are listed and explained, indicating the culprit.

ANYONE WHO HASN'T YET DONE SO, DON'T READ IT NOW, AND IF AT ALL, DO SO AFTER READING CARR'S NOVEL.

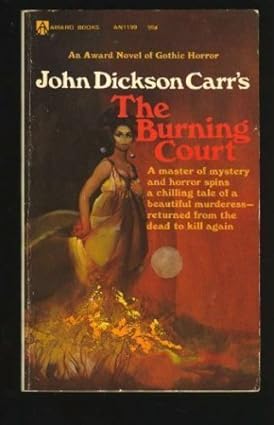

The novel dates back to 1937, and Carr's greatest masterpieces date back to the mid-1930s. That same year, Carr published a work that exists in two versions, one as a short story and the other as a novella: The Third Bullet, which is somehow related to the first; the novel in the Merrivale series, The Peacock Feather Murders; and the supernatural tale, Blind Man's Hood. Three emblematic works, which perfectly complement The Burning Court.

First of all, why did Carr title his novel that? The English title is an exact translation of the original French title: La chambre ardente. What was La Chambre Ardente? It was a special court in France that adjudicated exceptional cases and therefore exercised exceptional powers: it was so called because the room in question was always lit, day and night, by torches. He first dealt with the trial of the Huguenots, then with the Poison Affair, and finally with verifying the correctness of the Fermiers généraux (the territorial tax collectors who, on behalf of the state, collected taxes from the population). The Poison Affair was the conspiracy uncovered following the death of Gaudin de Sainte-Croix, which directly implicated Marie d'Aubray, the Marquise of Brinvilliers. Following the investigations of Gabriel Nicolas de la Reynie, chief of police of France, a vast network of poisoners, who had eliminated family members without first arousing suspicion, was dismantled. Numerous aristocrats were executed. The affair culminated with the arrest of La Voisin, who implicated unworthy nobles, abbots, and priests who organized Black Masses, murdered newborns (including those resulting from abortions) and disposed of in crematoria, and desecrated consecrated hosts. La Voisin, who was never tortured for fear that under torture she would reveal the names of aristocrats at the Royal Court, was burned as a witch in 1680. Only after her death did news emerge of Montespan (Louis XIV's mistress) and her possible attempt at regicide using poison (a matter that was hushed up because it would have implicated many other aristocrats and sparked a very dangerous scandal).

Carr then titles one of his novels, linking it to the Poison Affair and its origins, and thus to the Marquise de Brinvilliers, a historical figure, lover of the Chevalier Gaudin de Sainte-Croix, who supposedly learned how to manipulate certain poisonous substances in the Bastille to produce poisons. Through him, she allegedly killed her father (who had previously had Gaudin arrested and imprisoned in the Bastille), two of her brothers, and attempted to kill her sister and her husband, the Marquis Antoine Gobelins de Brinvilliers (the Gobelins were the historic tapestry makers). Brinvilliers was arrested after her lover died during an experiment, when his glass mask broke and he inhaled deadly vapors, and after a series of letters directly implicating her were found. Hence, she was arrested and accused of necromantic practices and witchcraft, and sentenced to torture. Brinvillers was burned in 1676.

The novel opens with Edward Stevens, a consultant for a publishing house that is due to publish Gaudan Cross's new book on famous trials. While leafing through the manuscript on the train, he is shocked by the photo of a certain Marie d'Aubray, guillotined in 1861, because that woman is his wife, Marie. Edward lives with his wife in a cottage near the Despard estate, whose founder had been a man very close to Brinvilliers. The last of the Despards, Miles, lives on the estate after years of living abroad, along with three nieces and nephews, the children of a brother: Mark, Ogden, and Edith. Mark is married to Lucy; the other two are single. Suffering from gastroenteritis, a disease caused by his excessive lifestyle, Miles died two weeks earlier. At the Despard house, Ted finds not only his friend Mark, but also Tom Partington, a doctor and Mark's childhood friend, who had had an affair with Edith years earlier, before being forced to flee for performing an abortion on the girl who assisted him in his practice. Tom has returned, at risk of arrest, because his friend Mark, who is seriously worried, has called him back: he is convinced that his uncle was killed by arsenic and that some infernal plot is afoot. Near him, a string with nine knots was found, a detail suggestive of witches, and on the closet floor he found a glass into which milk had been poured, and an antique silver cup containing a strange mixture of egg yolk, milk, and port. In addition to Edith's cat, which probably died of poisoning, he has had the two artifacts examined, which has revealed that the cup contains two grains of arsenic. Meanwhile, at the Stevens house, someone opened the bag containing Gaudan Cross's manuscript and made disappear first the compromising photo, and then the entire chapter relating to the execution of Marie d'Aubray in 1861.

Mark manages to convince Ted and Tom to accompany him, along with Butler Henderson, to the family crypt, where Miles was buried in a wooden coffin, unlike all his ancestors, who were buried in steel coffins. He believes he can find evidence indicating arsenic was the cause of death. However, the surprise that grips everyone is that the body of old Miles (only 56 years old!) is missing: yet the crypt is made of granite, and to access it, they had to break some stones and then lift a heavy stone slab that hides the entrance to the underground chamber. Where did Miles go?

Meanwhile, at the Despard house, a new case breaks out: Mrs. Henderson, the housekeeper, claims that on the night of Miles's death, she saw a woman through a crack outside Miles's bedroom door, wearing a dress very similar to one worn by a disfigured figure in a painting in the villa, which is assumed to have been that of the Marquise de Brinvilliers. That very night, Lucy, Edith, and Mark were at a masquerade ball, the nurse, Miss Corbett, was at a friend's house, and Ted and Marie were at their cottage, and Lucy was wearing a dress exactly like the one sported by the mysterious visitor. The woman in the room is moving strangely, and her head appears to be disconnected from her neck. At one point, after giving Miles a cup, she exited through a door that hadn't existed for two hundred years, when the part through which it communicated was destroyed in a fire. To test the woman's very strange statements and dispel any doubt, an axe is used to see if the door between the two windows actually exists, but instead, a passage opens onto the outside of the villa.

Meanwhile, the writer Gaudan Cross has appeared, and Marie, under suspicion due to her resemblance to D'Aubray, leaves the house and goes to visit Gaudan. Some of those present, especially Edith and Ogden, are suspicious of Marie, based on a series of clues suggesting the reincarnation of the undead. One of these could be Marie, assuming one believes in fantastical hypotheses.

Inspector Frank Brennan, who coordinated the investigation, is at a loss to explain the disappearance of the body and the supposed presence of an undead, namely the mysterious veiled woman. He will be saved by Gaudan, an old acquaintance of his, who will develop a hypothesis capable of explaining all the strange and mysterious events that have occurred up to that point.

I will separate the two solutions provided by Carr and mention a third one included in his essay by Doug Greene.

1st SOLUTION: RATIONAL

Essentially, Gaudan Cross accuses the nurse, Miss Corbett, of murder. She is none other than Jeannette White, who has returned and has rekindled her relationship with Mark Despard, plotting with him to murder old Miles so that Mark can inherit his fortune. Essentially, the ghost woman could be explained by old Miles's obsession with locking himself in his room every evening and trying on clothes he had stored in the closet. To do so, since the lighting in the room was dim, he would move the dresser with the mirror to the center, between the two windows, where a lamp hung. Thus, Mrs. Henderson would have seen the figure reflected in the mirror, exiting not through an imaginary door but through the connecting door between Miles's room and that of the nurse. By her own admission, the nurse had placed the internal bolt between the two rooms and changed the external lock on the corridor, so she could be alone at the right time to make a dress exactly like Lucy's. Meanwhile, Mark has escaped, and no one knows where he ended up when the affair between him and the nurse became known. Mark, in turn, had been accused of the disappearance of the body. Why? Because despite being complicit in Miles's murder, while he wanted to kill his uncle with arsenic but blame the cause on gastroenteritis, Myra's goal was different: she aimed to frame poor Lucy for the murder, getting rid of her wife and thus joining Mark forever. However, he doesn't harbor the same hatred for Lucy and therefore wants to save her. And to do this, after creating a mystery, she convinces her friends of the need to exhume Miles's body to prove his poisoning: this only to reveal that the body has disappeared from the crypt. In reality, in Gaudan's reconstruction, he was the one who hid it, an instant after the coffin was placed in the niche: under the pretext of wanting a moment alone with his uncle, in one minute (I repeat, one minute!) he moved the coffin from the niche, opened the coffin, took the body, opened one of the two marble urns in the crypt where the flowers were placed, placed the body inside after taking some flowers and throwing them on the floor, closed the urn, closed the coffin, and placed it back in the niche. All this in one minute! Then, when Ted and Parrington are sent to the house to get two stepladders (probably to place the empty coffin on), Mark tells Henderson to get the tarpaulin from the tennis court, to cover the opening leading from the chapel floor to the crypt, using four large stones placed at the corners. And as he leaves, he takes the body from the urn and places it at Henderson's house, thinking that Henderson will take longer and he can calmly dispose of the body in the boiler. But Henderson's unexpected arrival forces him to improvise, placing the body in the rocking chair, lifting the corpse's whitish hand and waving it as if to greet poor Henderson, who will claim to have seen Miles alive.

2nd SOLUTION: FANTASTIC

Alongside this rational solution, which involves Myra Corbett, aided according to him by Mark, in the Epilogue, Carr follows up with an absolutely irrational solution, based on the fact that one of the characters in the story (Marie) is the reincarnation of the Marquise de Brinvilliers, wants to turn Edward into an undead, has killed Gaudan Cross, who was the reincarnation of Gaudin de Sainte-Crox and who wanted to return to being her lover (but unfortunately he was old and did not realise that Marie loves Ted), that he cannot die (since he too is undead) and will therefore return under another identity, and has arranged for Myra to be accused of having murdered Miles in his place, while Mark ran away and no one knows what happened to him: he ran away when it was discovered that he had resumed his relationship a year earlier with Jeannette White, the girl on whom Partington had performed an abortion years before (the child she was pregnant with was most likely Mark's), who reappeared as Myra Corbett, Miles' nurse. Furthermore, Miles' disappearance is due to the fact that he himself is undead, while Mark's disappearance, still alive, can, in my opinion, be explained by the fact that he was eliminated and thrown into the boiler. According to this reconstruction, just as it is plausible that the woman seen by Mrs. Henderson is Marie (Ted's wife), dressed like her ancestor, and that she really did emerge from a door that no longer exists, it is also plausible that Miles disappeared from the crypt, because, as Marie had predicted when she learned they would descend into the crypt, "you will not find Miles in the coffin." According to this reconstruction, Marie's terror of funnels would also be explained, as would the fact that all of Paul Desprez's descendants have arranged to be buried in steel coffins, a material witches dislike, and the discovery of cords with nine knots, even in Miles's coffin.

Another detail worth considering is the wooden coffin. Notice that when the four descend into the crypt, in the light of Mark's flashlight, they see niches containing steel coffins and a single wooden coffin, Miles's. According to Mark's explanation, it was Miles who shouted that he wanted a wooden coffin and had him promise Mark that a wooden coffin would be there to receive his body. So we have two very distinct facts: the steel coffins and the wooden coffin. Let's ask ourselves: why the steel coffins? We're told that witches don't like steel and stone but adore wood. So all of Paul Desprez's descendants, including himself, were afraid that the witches might disturb their dream. And this insinuates something supernatural into the story. Miles wanted the wooden coffin. He had spent a long time abroad (in France?): had he encountered any undead? Had he himself become undead? Is that why he wanted the wooden coffin? If we accept the fantastical solution, it might be acceptable. But... there's a but. We know all this from Mark's words: what if Mark had instead reported these words attributing them to Miles only because a wooden coffin, besides being much lighter than a steel one, would have been easier to open quickly? In this case, we see that the same statement and the same state of affairs can support two possible solutions and explain certain things. Here, however, even if we attribute Miles' request to Mark's specific desire to muddy the waters, we are still faced with the reality of a row of steel coffins that pre-existed whatever happened or didn't happen to Miles. So, essentially, once again, the possibility of the supernatural is left there to give rise to thought. Regarding all this and the replacement of Francois Desgrais-Desgrez with Paul Desprez, Dan Napolitano, who will be editing the upcoming publication of The Burning Court by Crippen & Landru, with various notes and digressions, told me that "It's possible that JDC was playing with his readers who were more attentive to historical details, e.g., people like you and me, and that it's a clue" and that "In the forthcoming book from C&L, in one of the commentaries, I discuss the business about the wood coffin, including JDC's inspirations and source materials. You're right, this is a very important little detail." If this was Carr's game with his readers, who were more attentive to historical details, another detail also belongs to this game, one that most people will have missed: Gaudan Cross, before his solution, claims to have been imprisoned for several years for a crime he committed, and that, thanks to the prison director's indulgence, he was able to read extensively about the major trials of the past, using the prison library. Now, this is his version, if we accept his rational solution; and indeed, his history with Frank Brennan indicates that he must have become something of an expert, one the police must have called upon on several occasions. However, if we were to see Gaudan as an Undead, a reincarnation of Gaudin de Sainte-Crox, his confession of having been incarcerated would take on a different aura: in fact, Gaudin was incarcerated in the Bastille, before he and the Marquise de Brinvilliers decided to poison a series of people. That is, essentially, the same statement, without being modified with lies, can be valid for both solutions, depending on how you accept it.

3rd SOLUTION: in the appendix to the long essay by Douglas Greene

Doug published in the appendix to his famous essay on Carr, "The Man Who Explained Miracles," a third solution, suggested by his brother: Marie was not a witch, a reincarnation of d'Aubray, but was actually mad, and as such, her desire to turn Ted into an undead would have been the ravings of a madman. In fact, many years later (36!), Ted would still not have died and become an undead, but would still be alive. The reason is that, by setting the story in 1937 in 1929, Edward Stevens finds himself in a 1965 novel, Panic in Box C.

This connection is strange: a character appears in two different novels! In any case, I would separate this fact from the novel in question, and attribute it to a broader process followed by Carr (and other writers, first and foremost Ellery Queen) whereby the same character or a specific situation appears in at least two different novels, even belonging to different series, as if to create a texture, a secret yet present design, that links various narrative moments together. I don't know how, however, to explain it: Edward Stevens appears in The Burning Court and Panic in Box C (Fell series); Jeff Marle is present in The Lost Gallows (Bencolin series) and in Poison in Jest; Sir James Landevorne is a recurring character in the Bencolin series: in the stories "The Shadow of the Goat," "The Ends of the Justice," "The Murder in Number Four," and in the novel "The Last Gallows"; Patrick Butler in Below Suspicion (Fell series) and "Patrick Butler for the Defense"; Grimaud appears in "The Three Coffins" (Fell series) and is mentioned here in "The Burning Court."

We mentioned at the beginning that Carr drew inspiration from the story of the Marquise de Brinvilliers, transferring some characters into his novel, appropriately linguistically transformed: Marie d'Aubray is the Marquise, but she is also a woman accused of murder in 1861 and would still be accused of murder now (Gaudan Cross in his explanation says that she is not actually Marie d'Aubray, but is a foundling who was adopted precisely because of her great resemblance to d'Aubray), Gaudan Cross would be the reincarnation of Gaudin de Sainte-Croix, and Desprez, Paul Desprez the forefather of the Despard family (Desprez had been anglicized to Despard) we read that in the distant past he had been in contact with Madame la Marquise. Here, however, we see a strange, very strange inconsistency: John Dickson Carr is famous as a writer for always being extremely well-researched, especially when writing historical plots. This is not a historical novel, but historical references abound. Where would he have found them? First of all, in Dumas père, who wrote The Marquise de Brinvilliers, in which he recounted the story of the murderess and necromancer. And also in a story by Conan Doyle, "The Leather Funnel" (1900). Doyle's tale is dark and oppressive, and is well-suited to a story filled with suffering, such as the Marquise's crimes and the water torture she endured (in "The Burning Court," we read that Marie was frightened only by the sight of the funnel). Meanwhile, Dumas père's long story is also ironic and full of verve. Conan Doyle's story was likely written in the wake of the emotions he felt reading Dumas père's.

In Dumas père's long tale, we read not only of the exploits of a dissolute woman, who reacted to her husband's growing indifference, even sexually, by collecting lovers (a second cousin, the Marquis de Nadaillac, with whom she had sinned two hundred times; a servant, La Chaussée, also an expert in poisons; and her children's tutor, Briancourt), but also of the murderous exploits of Brinvilliers and her lover, the Chevalier Gaudin de Sainte-Croix. Their murder was put to an end by a handsome royal officer, one François Desgrais, who, after Gaudin's accidental death, sought to arrest her. She had fled first to England and then to a convent in Liège, where she could not be touched by secular power. By virtue of her masculine beauty, to which the Marquise was not indifferent, he disguised himself as a priest, lured her outside the convent, and there had her surrounded by men-at-arms and arrested. Desgrais himself found evidence of the Marquise's guilt in a bundle of papers where she herself, in tiny handwriting, had confessed to all her misdeeds. Well, in Dumas père's story, Desgrais is mentioned alongside the others, both perpetrators and victims. And some of these, with their original names, are cited by Carr, but not Desgrais, who instead becomes Desprez: why? Yet Carr was extremely meticulous when researching his mystery novels set in another era. But here, however, he doesn't use the original surname. I thought there had been an error during the transition from typing to publication, and a Desgrais-Desgrez could have become a Desprez. And I asked Doug Greene, who was also open to the possibility, but to cut the wool over his eyes, he sent me to ask another expert, Dan Napolitano, who was immediately intrigued by the question. And he gave me an answer that raises another question: the first coffin, that of the founder of the house, was not Francois Desprez (and then in that case I would have been right) but Paul Desprez. In other words, another person. Perhaps when Desprez came to America, he had actually changed his surname, and Paul was his descendant or a close relative, perhaps his brother, who knows. Or perhaps Paul was Francois himself, who had changed his surname to take a breather from the witch's posthumous revenge. And this would explain the use of steel for the coffins of Paul's descendants. While the wooden coffin, which had been Miles's wish, could be explained by his changed spirit. Hadn't he been the one to express his doubts that creatures could exist that were neither alive nor dead, but were a kind of Undead? Had he had direct experience that convinced him of their existence?

Another reason for accepting the fantastical solution is Marie's irrational fear of funnels. Why? It recalls the torture she had been subjected to, the water torture known as "Question donné avec l'eau": the criminal was tied to a rack, and water was forced down liters through a funnel. The torture could be ordinary (a rack about 60 cm high and 6 liters of water or other liquids, even urine) or extraordinary (a rack over 1 meter high and 12 liters of water). In the case of the Marquise, due to the enormity of her crimes, it was decided that she should undergo both. Despite the treatment, she did not confess anything else. After ingesting so much water (her stomach had become frighteningly swollen), the condemned man was bundled up, tied up, and placed near the fire. However, it seems that Brinvilliers, upon entering the torture chamber, had boldly expressed her opinion on those buckets full of water, which would have been used on another occasion for bathing. And then there is the recurring appearance of nine-knotted cords, magical objects belonging to witches. But what most conspires to establish the reader's greater attraction to the fantastical solution over the rational one is that Gaudan's solution relies on excessively short timeframes, declaring them to be sufficient to carry out a series of actions that perhaps not even Flash Gordon would have been able to accomplish in the announced timeframe. And then why does Marie, leaving her home, even knowing that she will draw the attention of everyone involved in the drama to her, go to visit Gaudan? Too many unanswered questions, which allow the reader (in my opinion) to accept the fantastical solution with greater conviction.

The third solution, on the other hand, is almost a divertissement. He hypothesizes Marie's insanity (thus eschewing the first, rational, one), explaining the chain of murders not by her belonging to an amoral entity, reincarnated, never fully dying, but by her insanity, explaining it by the fact that Edward, 36 years later, would not have died, or at least would not have become undead, appearing as a character in Gideon Fell's novel of the final Carrian narrative.

This is my opinion of the solution. But the novel is not just this, or rather, it is not only aimed at this. It is also the way in which Carr, once again, explores a time not his own, with a truly astonishing mastery of history and alternative sources. He always maintains the tension at a very high level.

Carr is an absolute master of psychological insight, historical research, and historically-setting his novels, as well as solving seemingly impossible crimes. But beyond that, his novels are enthralling because his writing and his ability to generate tension are masterful. In the past, whenever I've had the opportunity, I've delighted in identifying ways to generate emotional tension in his novels. His methods are those of the fathers of crime fiction, quite different from contemporary ones. Here I recognized one, which I discussed and I introduced his first novel with Bencolin: essentially, when Carr describes a certain situation to build tension and bring it to a spasmodic level, he can't stick to the same path for long, but must use the rubber band technique: stretching, then stopping, then giving it another tug, then stopping again and perhaps retracing his steps, only to return and give it one last tug. In this way, he manages to keep the reader glued until he reaches the climax, the apex of his scene. This happens in the scene where Miles dies and first asks for a wooden coffin: the climax is the discovery of the dead cat in the closet next to the famous cup with the concoction; it happens in the scene where Mrs. Henderson watches from the curtain on the verandah's French window what happens inside Miles' room before he feels the fatal abdominal pains, and the climax is that the mysterious visitor's neck does not appear to be fully supported by the body. In both cases and in many other scenes, Carr does not say at the climax what it represents, but he allows the reader to understand it, based on what he has hinted before: the dead cat presupposes poisoning by something, the neck brings to mind the Marquise de Brinvilliers, who was beheaded before being burned. In this way, by not explaining something himself, but by making the reader understand it, he also keeps the tension high, because he establishes something ambiguous: it's not the writer who closes a situation by defining what is or isn't, but rather he makes the reader the interpreter, who, since he's not the writer, must also take into account the possibility of being mistaken in attributing something to someone. Thus, in the case of the neck not perfectly attached to the neck, the reader is led to believe it's a supernatural apparition, forgetting that everything is in Mrs. Henderson's words, and therefore she may have overindulged in her imagination.

In this mysterious historical milieu, the characters that emerge most are the female ones: all strong women, from Marie (whether you look at her as a witch or as an orphan found at the center of machinations beyond her control), to Lucy (mistaken as a ghostly woman present in Miles' room before his death), to Edith (the woman outraged by Tom's actions years earlier, when she performed an abortion, ending their love story), to Myra (the woman on whom Tom performed the abortion, who got rid of the fetus probably the result of her relationship with Mark). Of the four, from whatever angle you look at it, the ones who present the most grey areas are Marie and Edith: while Marie never refers to her reincarnated nature (but is deeply interested in Gaudan's manuscript, so much so that she opens her husband's bag to read the most interesting parts), she is nevertheless terrified of such an innocent instrument as a funnel; Edith, on the other hand, repeatedly highlights the sources of an undead literature, and at the same time (a detail that emerges extemporaneously) we learn that it was she who procured the arsenic to eliminate rats.

The male characters, on the other hand, never manage to assert themselves over the events and the women present in the narrative: they are weak. From Edward who doesn't know what to think of Marie (sometimes he responds to the accusations instinctively, not fully convinced), to Tom (who hides from everyone that Myra is the girl on whom he had performed the abortion, and who prefers to disappear and destroy his relationship with Edith rather than "disgrace" his friend Mark (but what kind of man is he?), to Mark who in everything he does, never behaves in a crystalline way, but says and doesn't say, affirms and lies, and most of the time is reticent about what he does (he has been in a relationship with Myra for more than a year while continuing to live with and lie to Lucy, he doesn't want to say what relations his ancestor Paul Desprez had with the Marquise de Brinvilliers, etc..). The only male who has a strong position and aura is Gaudan, who however lives a tragedy that is not only personal (poisoned by cyanide) but is also the tragedy of the mystery novel: it is the first case but not the only one, one can say. That is, in which the detective, the hero of a story, dies, leaving the epilogue mutilated (and in this ambiguous state, the fantastic alternative ending fits in well).

In a certain sense, the death of the detective (which, if we want, is not entirely unique: Poirot also dies at the end of Curtain, even though the plot never touches on the supernatural) in a novel where the fantastic repeatedly emerges and leaves the reader speechless, the disappearance of a woman in ancient costumes through a door bricked up centuries earlier, behind which lies the villa's external perimeter wall, the disappearance of a corpse from a sealed crypt, will lead Todorov to say that this is one of the very few cases in which the reader's sense of estrangement emerges, in the mystery novel, which is normally a rational novel, so that at that moment it is said that we are in a fantasy novel.

"Il est un auteur qui mérite qu’on s’y arrête plus longuement, quand on traite de la relation entre romans policiers et histoires fantastiques : c’est John Dickson Carr ; et il y a dans son œuvre un livre qui pose le problème d’une manière exemplaire : la Chambre ardente. De même que dans le roman d’Agatha Christie, on est placé ici devant un problème en apparence insoluble pour la raison : quatre hommes ouvrent une crypte, où l’on a déposé quelques jours plus tôt un cadavre ; or, la crypte est vide, et il n’est pas possible que quelqu’un l’ait ouverte entre-temps. Il y a plus : tout au long de 1 histoire, on parle de fantômes et de phénomènes surnaturels. Le crime qui a eu lieu a un témoin, et ce témoin affirme avoir vu la meurtrière quitter la chambre de la victime en traversant le mur, à un endroit où une porte existait deux cents ans aupa¬ ravant. D’autre part, l’une des personnes impliquées dans l’affaire, une jeune femme, croit elle-même être une sorcière, plus exactement une empoisonneuse (le meurtre était dû au poison) qui appartiendrait à un type particulier d’êtres humains : les non-morts. « En bref, les non-morts sont ces personnes — principalement des femmes — qui ont été condamnées à mort pour crime d’empoisonnement, et dont les corps ont été brûlés sur le bûcher, morts ou vifs », apprend-on plus tard (p. 167). Or, en feuilletant un manuscrit qu’il a reçu de la maison d’édition où il travaille, Stevens, le mari de cette femme, tombe sur une photographie dont la légende est : Marie d’Aubray, guillotinée pour meurtre en 1861. Le texte continue : « C’était une photographie de la propre femme de Stevens » (p. 18). Comment la jeune femme pourrait-elle être, quelque soixante-dix ans plus tard, la même personne qu’une célèbre empoisonneuse du XIXe siècle, et de surcroît guillotinée ? Très facilement, à en croire la femme de Stevens, qui est prête à assumer les responsabilités du meurtre actuel. Une série d’autres coïncidences semble confirmer la présence du surnaturel. Enfin, un détective arrive et tout commence à s’éclaircir. La femme qu’on avait vue traverser le mur, c’était une illusion des sens provoquée par un miroir. Le cadavre n’avait pas disparu mais était habilement caché. La jeune Marie Stevens n’avait rien de commun avec des empoisonneuses mortes depuis longtemps, bien qu’on ait essayé de le lui faire croire. Toute l’atmosphère de surnaturel avait été créée par le meurtrier pour embrouiller l’affaire, détourner les soupçons. Les véritables coupables sont découverts, même si on ne réussit pas à les punir. Vient un épilogue grâce auquel La Chambre ardente sort de la classe des romans poüciers qui évoquent simplement le surnaturel, pour entrer dans celle des récits fantastiques. On voit à nouveau Marie, dans la maison, repenser à l’affaire ; et le fantastique resurgit. Marie affirme (au lecteur) que c’est bien elle l’empoisonneuse, que le détective était en fait son ami (ce qui n’est pas faux) et qu’il a donné toute l’explication rationnelle pour la sauver, elle, Marie (« Il a vraiment été très habile de leur fournir une explication, un raisonnement tenant compte des trois dimensions seulement et de l’obstacle des murs de pierre », p. 237). Le monde des non-morts reprend ses droits, et le fantastique avec lui : nous sommes en pleine hésitation sur la solution à choisir. Mais il faut bien voir que, finalement, il s’agit moins ici d’une ressemblance entre deux genres que de leur synthèse. Passons maintenant de l’autre côté de cette ligne médiane que nous avons appelée le fantastique. Nous sommes dans lé fantastique-merveilleux, autrement dit, dans la classe des récits qui se présentent comme fantastiques et qui se terminent par une acceptation du surnaturel. Ce sont là les récits les plus proches du fantastique pur, car celui-ci, du fait même qu’il demeure non expüqué, non rationalisé, nous suggère bien l’existence du surnaturel. La limite entre les deux sera donc incertaine ; néanmoins la présence ou l’absence de certains détails permettra toujours de décider".(Cvetan Todorov, Introduction à la littérature fantastique, 1970).

So, stylistically speaking, this novel can rightly be considered a true masterpiece, and a cornerstone of mystery literature. And within Carr's literary output, this is undoubtedly the best novel without a recurring character.

Pietro De Palma

No comments:

Post a Comment