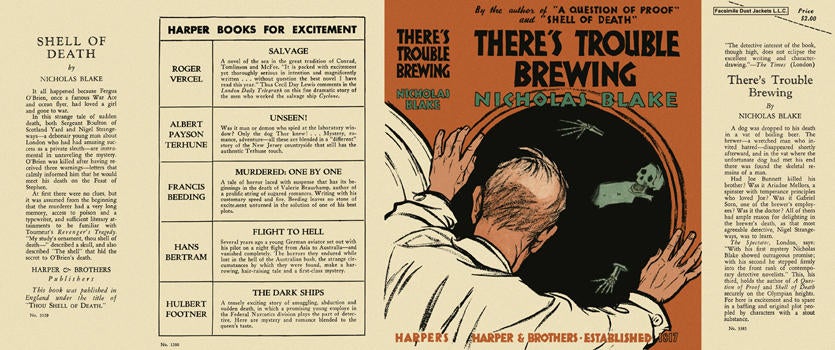

There’s Trouble Brewing, 1937, is the third novel with Nigel Strangeways as the main character. It is beautiful, certainly interesting, but it is certainly not a masterpiece. If anything, it is very interesting for certain programmatic positions that Nigel Strangeways shares with other colleagues of the period. The novel begins quietly: Nigel Strangeways has been invited to hold a conference on poetry in the town of a couple of friends. A varied fauna of people participate in the conference: from Arianna Mellors, an exuberant virago, to the poet Gabriel Sorn, to Eustace Bennet, the father-master who makes the bad weather in that town, since he founded and manages a brewery, which gives work to several citizens. A particular tension immediately arises around Eustace, and Nigel is convinced that that character is anything but loved in those parts. Furthermore, the industrialist does everything to contact him, but not in the guise of a poet and critic, but rather as an investigator (for which Nigel is already universally known): he will have to shed light on the death of Tartuffe, his dog, who died horribly.

Eustace Bennet mistreats everyone he comes into contact with, selfish and egocentric to the utmost degree as he is. He even mistreats his dog, who, despite all the kicks and scoldings he receives from his master, always wags his tail near him, happy to be in his company. However, no one knows how, Tartuffe ended up in the pressure cooker, where he was boiled... alive. But whoever thinks that even in such a dry man there must be a glimmer of tenderness, if after the kicks he regularly gave him, he now feels the need to investigate the death of his dog, must think again: Eustace considered the dog his own, and as such it was his right to kick it, insult it, mistreat it in the same way he did with his wife, another of his properties, and therefore he wants to prosecute whoever took away his way to vent. Even reluctantly, Nigel must accept the job that the industrialist pays him and get to work: he will have to question whoever saw the dog, reconstruct its movements and understand who could have had the idea of making it die a horrible death, boiled alive in the master's beer factory. But on the day that Nigel has the entire factory at his disposal, a terrible discovery will be made: in the copper barley boiler, the completely fleshless and cleaned skeleton of a man is found who, from the finds (watch, dentures and something else), and from the hair that the skull still has, is recognized as that of the factory's owner, Eustace Bennnet.

At this point the question arises, since the deaths of the dog and its owner are absolutely the same, and occurred in the same way and in the same place, whether they were both planned and carried out by the same person/people or whether they are the product of two separate acts, by two different wills.

The second question is obviously who could have killed Eustace and why.

There are many people who wanted him dead: an anonymous letter in which sugar and stolen beer cases are mentioned would indicate the responsible party as the caretaker of the establishment, Lock, who could have hidden his shady business by killing his boss once he had been discovered (but then it turns out that he is an old soldier, upright and very loyal to his master); his wife, who does not seem very sorry about his death; his brother Joe, who is away on his boat, who would like to transform the factory but instead cannot do so because of Eustace's opposition, and who was once even forced by his brother not to marry Arianna; Arianna herself, who is very bitter towards Joe's brother, because he prevented him from marrying her and therefore made it impossible for the two of them to have their own life together; the poet Gabriel Sorn, who composes surrealist poems, and who is torn apart by the antipathy he feels for Bennet who never misses an opportunity to pillory him and at the same time cannot say anything against or defend himself because Bennet is also his employer because he has created advertising slogans for him; Herbert and Sofia Cammison themselves who hate him, the first for reasons related to the terrible conditions in which he makes his employees work and the other because he even tried with her; even Barnes, the brewery manager, would profit from his disappearance, because it seems that another beer company has offered to buy Eustace's factory, and in that case he would delude himself into keeping his job (along with that of the other employees) and making the most of his skills. And then, many workers would like him dead: his favorite pastime was to walk with a stealthy step, following a certain worker, without being noticed and watching him in silence, from behind, even for hours, until the worker at the height of the pressure, feeling observed, made a mistake and ended up being scolded and humiliated.

When the will is opened, it will be seen that the wife is not recognized as having left any legacy, while a third is left to her brother Joe and even two thirds to… Gabriel Sorn’s mother, who at that point becomes very important among the possible suspects, since in addition to inheriting, she could have killed Eustace out of resentment for not having been accepted even as an illegitimate son (Bennet had a youthful affair with Sorn’s mother, Emily, and he has certain features of his father).

However, the way in which Eustace was killed is also important: why in the pressure cooker and not kill him in another way? To eliminate traces from which the murderer could have been traced (poison, dagger, acid, bullets, considering that no cartridge was found in the filter of the coil)? Or for something else?

And was the crime premeditated or not? And was it carried out in the factory or elsewhere and then the body taken there?

The series of questions that are brought forward in the novel is not insignificant, but the novel's originality lies precisely in the examination of these secondary aspects, since the astute reader, quite astute, manages to understand who the culprit is at least sixty pages before the revelation (even though I managed to do it at least one hundred and fifty, and it is not difficult for others to do the same).

The most interesting things in my opinion are: among the clues, the fragment of green stone that Nigel unconsciously collected in the freezer and that will prove useful for the investigation, and also the chocolate cake and the donuts that disappeared from Eustace's house, that a thief in possession of the keys to the same (certainly his murderer) stole at night, disdaining instead the roast, food choices that have to do with weak teeth and the use of dentures; instead among the intuitions, the four identical signs that Niger finds on the floor of Joe's house, from which he deduces that a chair was placed, and mounted on it, he finds a trap door in the ceiling that leads to an attic where someone slept, and ate the chocolate cake and the donuts. In the rest of Joe's house, everything is abandoned and covered with canvases, except his study where they find Arianna's body, disfigured by the fireplace poker. And then, following the testimony of a vagabond, they will track down Joe's boat, sunk and burned with a charred corpse on board.

Nigel's supreme intuition is however that concerning the identity of the murderer: today, when so many novels have passed like water under the bridge, that idea of Blake's would be laughable, because so many have used it; but back then it was probably more original. However, it is an idea that finds all its strength in the very question that remains throughout the novel, until the end, obviously for those who have not solved it before: why was Eustace killed in a pressure cooker? Why?

Apart from that, it remains a good novel. It does not particularly shine for the number of suspects, which here is particularly limited (and this undoubtedly has its determining weight in the discovery of the culprit quite a long time before the end of the story), but the dialogues are enjoyable and at the beginning of the fourth chapter we read a programmatic declaration that Cecil Day-Lewis alias Nicholas Blake makes his detective recite, which for me is one of the most interesting things in the novel because it places Nigel in the same light as Eustace.

‘But I don’t see why you want to hunt criminals. I’m sure you can’t enjoyit. You don’t have to for a living. Do you believe in Justice or something?’

Nigel was gazing non-committally down his nose. ‘Hallo, what’s this?’he said to himself. ‘What is making her attack me like this? What is she trying to hide from me—or from herself?’ He said to Mrs Cammison: ‘I don’t believe in justice in the abstract. Some crimes are “just” and some actions are criminal. I suppose I do it because criminal investigation gives one a unique opportunity of studying people in the nude, so to speak. People involved in a case—particularly murder—are always on the alert, on the defensive, and it’s when they’re trying to cover up one part of their mind that they expose the rest. Even quite normal people start behaving in the most abnormal way.’… There’s nothing inhuman about curiosity. And mine is only trained, scientific curiosity. I’m sorry, though; I’m upsetting you, talking like this. I’m not a monster, really. To tell you the truth, I’ve pretty well made up my mind not to touch this Bunnett affair. Whoever did him in had every excuse, I should think.’ (Chapter IV).

If this seems to us to be a programmatic declaration from an absolutely positivist spirit, in reality absolutely different and inspired by classical and humanistic education, another very interesting disquisition that Nigel makes a few pages earlier appears to us:

But that’s only sometimes. Why did you ever take it up?’‘Oh, something to do, I suppose. It seemed to be the only profession for which a classical education fitted one.’‘Now you are laughing at me. I’m quite serious.’‘So am I. It does. If ever, in your salad days—as one of my comic uncles calls them—you were compelled to do a Latin unseen, you’ll know that it presents an accurate parallel with criminal detection. You have a long sentence, full of inversions; just a jumble of words it looks at first. That is what a crime looks like at first sight, too. The subject is a murdered man; the verb is the modus operandi, the way the crime was committed; the object is the motive. Those are the three essentials of every sentence and every crime. First you find the subject, then you look for the verb, and the two of them lead you to the object. But you have not discovered the criminal—the meaning of the whole sentence yet. There are a number of subordinate clauses, which may be clues or red-herrings, and you’ve got to separate them from each other in your own mind and reconstruct them to fit and to amplify the meaning of the whole. It’s an exercise in analysis and synthesis—the very best training for detectives.’ (Chapter IV).

As any writer who has created a much-loved character with whom he identifies (Carr when he puts a similar declaration of intent in the mouth of Bencolin, or Crispin in Fen or Van Dine in Philo Vance, etc..) Blake also puts in the mouth of Nigel Strangeways his own declaration on what the detective must do and how he operates. In truth, the declaration, which betrays the academic origin of the author and all his classical studies, however integrates with the other passage (which completes the dialogue between Nigel and Sophie, in the following pages) to form a whole, in which the humanistic faculties combined with the capacity for analysis, serve to form a unique ability, that of the detective to know how to interpret in the most correct way all the information he takes possession of in order to put it to good use. But the humanistic faculties, let us see, he refers them to the study of Latin, which more than other languages, has a very strong logical connotation which is therefore very close to the mathematical-scientific one. Nigel's statement continues and clarifies how the detective must reconstruct the dynamics of the murder in order to catch the culprit.

But to return to classical education. You learn to write Latin and Greek compositions in the style of certain authors. The first thing you learn is that all the best authors are constantly breaking the rules of the grammar-books; each has his own idiosyncracies; and that is equally true of the criminal—the murderer in particular. To write a good Latin or Greek composition requires more than a superficial gift of mimicry; it requires that you should get right inside the head and the skin of your model. You’ve got to try and think and feel like Thucydides or Livy or Cicero or Sophocles or Virgil. Similarly, a detective has to get right inside the character of a criminal if he is successfully to reconstruct the crime.’ (Chapter IV).

How is Nigel similar to the owner of the pub, unbearable and evil, who persecutes everyone around him? In his way of relating: both he and Eustace wait for the other to make a mistake: he waits for the murderer to make a mistake, Eustace the employee; both are alert, waiting for the first mistake of the weak, to strike. Nigel and Eustace are practically the same, two sides of the same coin, the yin and the yang, the black and the white, the evil and the good, only that sometimes the good can become the evil and vice versa; it is enough just how you see it all. But the comparison can also become such in the fixed alternation of the two moments, of the two identities, of the two forces, of the two natures.

After all, this alternation of moments continues throughout the novel: there are dark moments and less dark moments. It is worth noting that the surprises always occur at times and in places where there is a strong contrast: the discovery of the skeleton occurs in a dark environment, where the light of the flashlight illuminates calcined, that is, white, bones; the discovery of Arianna's corpse, in an empty house, full of empty things, the only thing that is not empty is the armchair on which Arianna's horribly disfigured corpse is lying; in Joe's boat, "The Seagull", found during the day, half sunk, the corpse of Bloxam stands out, a sailor that Joe had taken with him. Another contrast: during the day, in full light, a corpse that has become black because it is charred. Furthermore, the two only women, present from the beginning to the end of the novel, Sophia and Arianna, seem to me to also be references: Sophie refers to Wisdom, and Arianna to the myth of Theseus, to the ball of yarn, to the reconquest of light compared to the darkness of the labyrinth (that is, to the reconquest of truth).

The first chapter, which runs from April 23 to July 16, opens in the original edition with a proverb: Dogs begin in jest and end in earnest. In truth, all 15 chapters that mark the story, from the day the body is found, July 17, to the day the murderer is identified, July 21, are introduced by a maxim, or a proverb, or a line from a poem or play (mostly Shakespeare), in relation to what is narrated in that chapter. The passages always have a latent sense of sarcastic irony, and make one understand the encyclopedic culture of Cecil Day Lewis, disguised by the pseudonym of Nicholas Blake. They are:

I April 23, July 16 Dogs begin in jest and end in earnest. PROVERB

II July 17, 8 a.m.–5.15 p.m. As he brews, so shall he drink. BEN JONSON

III July 17, 5.15–7.50 p.m.

When shall this slough of sense be cast,

This dust of thoughts be laid at last,

The man of flesh and soul be slain

And the man of bone remain? A. E. HOUSMAN

IV July 17, 8.55–10.30 p.m. One Pinch, a hungry lean-faced villain, A mere anatomy.

SHAKESPEARE, The Comedy of Errors

V July 18, 9.15–11 a.m. Watchman, what of the night? ISAIAH (xxi, 11)

VI July 18, 1.30–4.35 p.m. Let’s choose executors and talk of wills. SHAKESPEARE, King Richard II

VII July 18, 9–10.15 p.m. It was a maxim with Foxey—our revered father, gentlemen—‘Always suspect everybody!’ DICKENS, The Old Curiosity Shop

VIII July 19, 8.20–11.30 a.m. Surely the continual habit of dissimulation is but a weak and sluggish

cunning, and not greatly politic. BACON, The Advancement of Learning

IX July 19, 11.30 a.m.–1.20 p.m. I’ll example you with thievery. SHAKESPEARE, Timon of Athens

Frost and fraud have dirty ends. WILLIAM GURNALL, The Christian in Complete Armour

X July 19, 1.30–5.30 p.m. The lips that touch liquor shall never touch mine. TEMPERANCE BALLAD (nineteenth century)

XI July 20, 8-11.30 a.m. He that gropes in the dark finds that he would not. ENGLISH PROVERB

XII July 20, 11.30 a.m.–5.15 p.m. He holds him with his skinny hand, ‘There was a ship,’ quoth he.

COLERIDGE, ‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner’

XIII July 20, 7.30–9.17 p.m. And when I think upon a pot of beer. BYRON, Don Juan

XIV July 20, 9.20–11.20 p.m. Thy chase had a beast in view. DRYDEN

XV July 21, 8 p.m. Oh that this too, too solid flesh would melt! SHAKESPEARE, Hamlet.

The proverb reported at the beginning of the first chapter seems to me a caustic reference to the fate of Tartuffe, Eustace's dog (Tartuffe, besides being a name that indicates the ability to smell, can also be a reference to Molière's work, Tartuffe) who ended up boiled alive if he only wanted to play. The first chapter, however, reserves another surprise for us: a long sentence that also contains caricatural references to Hitler, Mussolini, and Mr. Baldwin (most likely, indeed certainly, it refers to Stanley Baldwin, English Prime Minister from 1935 to 1937): “His pusillanimous and shifty-looking terrier face appeared in every illustrated newspaper in the United Kingdom, ousting from the front page the not altogether dissimilar features of Hitler, the neurotic-bulldog expression of Mussolini, the sealed lips of Mr. Baldwin, and the unconcealed charms of bathing beauties”. The references to Hitler, Mussolini and Baldwin, who was reproached before his resignation for an excessive indulgence in the international positions of Hitler and Mussolini (especially the latter's Ethiopian enterprise), which Blake introduces in the speeches, can also be explained by the political positions of Cecil Day Lewis who at the time was a communist, like his friend Kingsley Amis.

Finally, I make a note: Cecil Day Lewis certainly loved Brahms' music. At Oxford, music was studied seriously (let us remember that Edmund Crispin was the pseudonym of Bruce Montgomery, a famous composer and performer of organ music, who graduated from Oxford). Proof of this is the fact that both in this novel and in The Beast Must Die, references to the German composer appear. In our novel, Strangeways, returning from the conference while accompanying Sophie Cammison (in the first chapter), whistles the Sapphic Ode op.94 n.4, a lied for voice and piano by Brahms: "What a queer mixture of straightforward and mysterious this woman was! Her talk of moonlight and shadows for some reason put Brahms’ ‘Sapphic Ode’ into Nigel’s head. He began to hum it gently". But also the last sentence of the novel The Beast Must Die, reads: In the first of Brahms’ four Serious Songs, he paraphrases Ecclesiastes 3, 19, as follows: ‘The beast must die, the man dieth also, yea both must die.’ Let that be the epitaph for George Rattery and Felix. The four Serious Songs are the Vier ernste Gesänge op.121, for alto or bass and piano by Johannes Brahms. The first of them Denn es gehet dem Menschen wie dem Vieh, has as its reference in Ecclesiastes, third chapter, verses 19-22: Denn es gehet dem Menschen (For it is man).

Pietro De Palma

In the middle there is a part of Nigel's own motivations that is repeated twice exactly the same.

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

DeleteThanks. I didn't notice the repetition.

ReplyDelete"Cecil Day Lewis who at the time was a communist, like his friend Kingsley Amis."

ReplyDeleteAmis was only about fourteen when There's Trouble Brewing was published, so it's unlikely he was a communist or that he and Day Lewis were friends then.

In 1937 the full vileness of Hitler wasn't recognised, so Baldwin was still popular for his appeasement policies.

I am not saying that at that time, Cecil Day Lewis and Amis were communists, I only said that Cecil Day Lewis was a communist, as Amis later was. Even though Amis, after the invasion of Prague if I remember correctly, moved to different positions. As regards British foreign policy during the war for the annexation of Ethiopia to Italy, by Mussolini, unofficially the British and French governments broke the economic sanctions, and continued to sell oil and war materials to Italy throughout the war. This I know. What does it mean in your opinion?

DeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

DeleteI remarked on the age difference between Day Lewia and Amis for other readers, who might have misread your comments. I think Day Lewis was never a very active communist and that he left after the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact.

DeleteWhen he was dying, Day Lewis and his family stayed with Amis and his wife, Elizabeth Jane Howard, Day Lewis's former lover. Day Lewis's doctor ordered Amis to limit his time with Day Lewis, as he made him laugh so hard he risked dying early!

I never said he was an active communist, I said that at the beginning of his career he was a communist. From 1935 to 1938 he was a member of the Communist Party of Great Britain. He was a communist like other Oxfordians, in love with the idea of communism, as intellectuals, only to reject it when Stalin arrived, with his own idea of communism, and with his repressions. And little by little he distanced himself from that youthful infatuation

Delete