June Thomson, a British writer, is remembered in the very recent The Life of Crime by Martin Edwards, only because at a certain point in her career she devoted herself to Sherlock Holmes, preparing her own anthology of Sherlockian apocrypha, also writing essays, an original one of which on Doctor Watson in his relationship with S.H. Holmes and Watson: A Study in Friendship (1995) and also publishing an apocryphal novel, Sherlock Holmes and the Lady in Black (2015). In reality, Thomson was already quite famous at home and abroad, for having created an acclaimed series of Mysteries with Chief Inspector Finch.

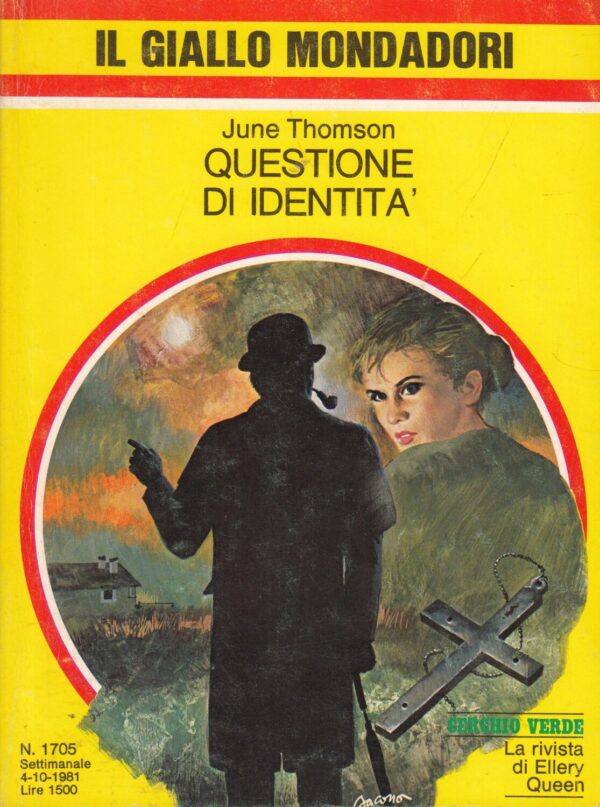

Born in 1930 and died in 2022, Thomson, after a life dedicated to teaching, began her successful series with Finch in 1971 with Not One of Us, which has a peculiarity compared to the rest of the production published in another edition, in the US: in the first title, Inspector Finch remains cited with his name, while from the second, Death Cap, it changes and we have Inspector Ruud while Sergeant Boyle is always his assistant. Why this? It's soon said. To avoid confusion with another Inspector Finch, who was the protagonist of Margaret Erskine's novels. In A Question of Identity, the fifth of the novels she wrote with Inspector Finch (in our case Ruud: the Italian edition is translated from the American one) the plot revolves around the discovery of a very decomposed corpse, in an abandoned field, where only cows graze, which one day finds itself being excavated for archaeological research. The almost skeletonized corpse has no way of being attributed to anyone in particular, because the fingertips have lost the ability to provide a fingerprint, due to the extreme decomposition, and the lack of teeth does not allow to trace a dental imprint. Furthermore, the body is covered with shreds of clothing, which do not allow to spread characteristics that can be recognized. The corpse is discovered to have been buried about two years before. The only strange thing is a chain, however, too deteriorated, found near the body. Furthermore, the body was buried with hands and arms crossed, and wrapped in a blanket as if it were a shroud. The land is owned by a certain Stebbing, who however purchased it relatively recently, after the presumed death of the unidentified individual. The attention of Inspector Ruud, in charge of the case, is therefore focused on the neighbor, the owner of the nearby farm, Geoff Lovell, who appears distrustful and reticent. Also living on the farm is a woman Betty Lovell, Geoff's sister-in-law, and her brother Charlie, a poor idiot, who would like to talk so much, but who is always put in a position not to communicate with the inspector.

So if the suspect n.1 is Lovell, we must still understand who the body could be. and so Ruud, digging into the Lovells' past, learns that Betty is the wife of the second brother, Ron. When he investigates this man, Ruud finds no photographs of him. Nobody knows what he looked like: he disappeared fifteen years ago, he couldn't stand his brother and his wife who was too Catholic, and he took up a wandering life, made up of petty crimes, women, and creating a reputation for himself as a petty criminal, violent. Ruud will eventually manage to contact a colleague of his who is looking for this Ron for attempted murder, and then an ex-flame of his Nancy, who will provide him with some photos, which will be crucial to understand, based on anthropometry, that the buried body is not Ron. Ruud will then start over again, returning to the place where he was found, and to the details already mentioned, and reflecting on the number of pillowcases he had seen Betty lay out, he will be able to solve the case. Reflecting in hindsight, precisely because of the investigation that starts from an unidentified corpse, I was struck by the closeness of this author to the novels of Hillary Waugh (Sleep Long, My Love, 1959 or Last Seen Wearing, 1952). In essence it is a quasi procedural: a close police investigation, with the help of scientific police components, and parallel investigations on possible attributions to some identity of the corpse, starting from a body so decomposed that it cannot be attributed, without error, to anyone in particular.

The extremely limited range of suspects would make one wonder whether the novel is predictable, which it is not: on the contrary, the characterization, which is intentionally one-sided, but which is then subverted with a twist, overturning all the acquired certainties, presents us with a story which, in some sense, rather than being a true mystery, is one of those novels called "Black", a dark story of crime and violence, which is not exactly a hard boiled. but not even a classic mystery, and it is placed in a halfway territory: violence is part of the novel, violence and oppression, but the investigation conducted by the policeman, if it is related to a police investigation tout court, is also a meticulous investigation in which ingenuity and psychology are not second: I was surprised by the reasoning on the pillowcases hanging out in the sun, which go unnoticed, until Ruud reflecting on it, understands why the farm is isolated, the dog is growling and always barks, Charlie wants to talk but is not given the chance, Ron's photos have almost all been destroyed, and a double-barreled shotgun is present in the places where characters live.

June Thomson is an author who deserves to be rediscovered: the psychological characterizations of secluded places, insert her "in a well-placed context: she digs into the respectability of society, to the roots of evil". The places where Finch acts are not in metropolises, but in the countryside (a very British characteristic), in the provinces, in isolated places. Mary Groff said years ago that "June Thomson's world is a world of solitude, of suspicions and victims who live in a mutual pact of rejection of society". The places of investigation are isolated, solitary almost to the point of misanthropy are the subjects of Finch's investigations, who in turn is a quiet and in a certain sense solitary policeman, living alone with a sister and a dog. The characterizations move in isolated places, where the communities that reside there are in a certain way the custodians, or believe themselves to be such, of ways of behaving that have their roots in time. Precisely in these communities the apparent composure hides instead a tangle of snakes (a characteristic that is found many times in British novels by Christie, Marsh, Allingham). In this Thomson inherits a way of writing that is typically mystery, even if with a more contemporary style.

Pietro De Palma