As many know, John Dickson Carr, while studying at Halverfordian College in Pennsylvania, wrote numerous short stories in the College magazine of which he was editor, The Halfervordian. In the context of the magazine, the stories are almost always exposed in the course of meetings between some characters, of which the main ones will also appear later in novels: this is the case, for example. by Bencolin and Sir John Landevorne. Among the stories enunciated in the Haverfordian stories there are the 4 of Bencolin collected later in The Door To Doom, but also other stories. This is the case in particular of a story, starring another of the characters who find themselves reunited by Sir John Landevorne, the freelance journalist and writer Stoneman Wood.

This story was later taken up several times by Carr, to testify how he probably intended to fully exploit the tragic and supernatural aura of the story. However, we note how the three drafts differ, even considerably, in relation to the use that the story had to be made of.

The first draft dates back to March 1927: in this case, part of the Haverfordian's New Canterbury Tales is the short story "The Legend of The Cane in the Dark". Given the unavailability of the story in publications, I will specify its content.

WARNING : SPOILERS !!!

Mr Stoneman Wood is a freelance writer and journalist. He and cousin Stephen are the sole heirs of Uncle Stoneman's fortune. After a trip to Canada, during which Wood was close to being killed by the guide who had mistaken him for a moose, he returns home, just to read in a newspaper that he himself died of a heart attack.

Once off the train, he sets off for home, but as he walks he hears the sound of a stick behind him: he turns and sees a tall figure wrapped in a black coat. And where he walks there is always this disturbing presence behind him with a walking stick, until he can't stand it anymore and runs towards the house, chased by the figure. He arrives in his room closes, but he smells a disgusting sweet smell, and in the dark touches a series of flowers. When he turns on the light again, the figure is there in front of the door asking him why there is a dead person in his bed. Wood, pulls the sheet away and sees someone who has been dead for some time who looks just like him.

Not understanding anything anymore, he throws himself out of the room in search of cousin Stephen, and if any of his family members appear outside the door of his room, for example. Aunt Miranda immediately closes it again in terror because she sees a ghost in him. When he finally finds his cousin Stephen, he takes the gun and points it at him, and he would also fire, if something behind Wood did not terrify him, to the point of convincing him to confess that he tried to have his cousin killed, to take possession of his fortune. which they inherited from their uncle, who died some time before, who always had a black coat and a cane with him.

After the cousin confessed - not only the attempt to kill his brother by means of a false guide, but also to have killed the double by simulating a heart attack, something certified by a doctor procured by Stephen himself (if he is a doctor and not just an impostor), in the absence of a family doctor, the otherworldly being - like Don Giovanni's Guest of Stone - leaves the scene, proud of having accomplished his mission: to protect his nephew from the greedy cousin he was looking for to kill him and have made sure that he confessed his guilt: in fact you can hear his footsteps that go down the stairs and then the shadow leaves the house.

THE END OF SPOILERS

When will Carr pick up the story and on what occasion? Eight years later, in 1935, Carr had the opportunity to sell the story to one of the magazines that published very strong stories, the Dime Mystery Magazine (which published tales of terror from 1932 to 1950. Its founder and editor, Harry Steeger, was deeply influenced by the Grand Guignol Theater in Paris, which offered shows based on stories of terror). In the thirties there were several American pulp magazines, which published stories with a very strong plot, which were based on various genres, from Sci-Fi, to Fantasy, from Western to Crime Fiction: they were magazines with sensationalist covers, with very bright colors.

Carr, who in 1935 was already "a name" among the new writers, thought it best to derive something from that story he had published eight years earlier, and which lent itself very well to being dramatized, appearing however under a pseudonym (John Dixon Carr ): a man who learns that he is dead, is chased by a supernatural creature, who thinks it is a real threat to him and who instead in the epilogue discovers that he was dead for others, who has returned from the afterlife only to to prevent a real villain from killing him.

Thus was born The Man Who Was Dead, then later reunited with other short stories, radio plays and essays by Carr in The Door To Doom. Of the three versions of the same story, according to many (and for me too), this is the best of the three: those who want to read it must get the volume The Door To Doom.

SPOILERS

Nicholas Lessing is a writer who suddenly became very rich, having inherited the fortune of an uncle he never met: he had previously fought in the First World War where he had suffered serious damage to his lungs from breathing asphyxiating gas. So the personal doctor had seriously advised him a trip by ship to Africa, where he would have to stay some time, to breathe pure air first while sailing and then on the African continent, so that he could heal. When he returns, eager to hug his fiancée Judith again, he gets off the steamer, takes the train to Waterloo station, and reads in the copy of the newspaper he bought, that he, Nicholas Lessing, died on March 15, the day before, for a chronic pleurisy, which would have been cured if instead of remaining in London, he had gone on the journey that his doctor had advised him, to breathe fresh air after a voyage at sea. How is it possible? He is alive and well! He then hurries back home, but loses his taxi and is therefore forced to use the subway, the one that his uncle from whom he had inherited, had defined "the road in the middle of hell". And so already when he makes the ticket, following the error of the conductor who made two, he begins to suspect that behind him there is someone or something threatening. Something that becomes more acute as he walks through the tunnels in search of the train, and which reaches the climax when already inside the car, he feels something or someone who, as if by scratching with his knuckles, tries to open the door of the car, but in vain. When the subway train arrives at Charing Cross, Lessing changes trains and is finally safe to be alone. Yet when the train enters a tunnel, he hears a noise as if something has entered through a window, and a strange smell. Then someone terrified enters his compartment who speaks of a very high presence, of someone blind who inspired terror, and begs him to go away with him.

Lessing returns home, which would later be the home of his uncle who died a year earlier, Douglas Lessing, to hug his girlfriend, who he had read in the article, had witnessed his death, along with his brother Stephen Lessing, and aunt Ann Handerson. He comes back thinking about who is following him and for what reason. When he enters his house, he smells of closed air, carpets and curtains and a sickening smell of flowers. Then he enters his room in the dark, and almost bumps into what he thinks is a table and which then realizes that it is a coffin, which contains the corpse of him, of a Nicholas Lessing, just like him. He runs away and goes to his aunt who sees him as a being from hell and locks herself in his room. The only one who believes him is his Judith. But in the meantime, the being who chases him has managed to climb the stairs: you can hear the stick that he holds, which touches the steps. Nicholas goes to his brother and finds him outside the door of his room, who looks at him with a mad expression of fear, not so much for him as for being behind Nicholas, a being from the Underworld for him, who throw on him. The two face off in the room which is locked from the inside and then a shot. When Nicholas Lessing breaks down the door, Stephen is dying from the bullet that shot himself in the chest and punctured the lung. He will confess that ...

THE END OF SPOILERS

In this story the uncle is not called Stoneman but Lessing, Douglas Lessing. He changes the name, but the story is always the same, so even here and in the third version that we will reconstruct later, the spirit of the Underworld is the Man of Stone. And in this story more than in the other days, there are many allusions to the Underworld.

The story The Man Who Was Dead, which is an authentic masterpiece of the supernatural, is structured in a very articulated way, so that the supernatural origin of being, who is then the dead uncle, is remarked in an obsessive way, by degrees. : first, Lessing thinks that something must have happened to the conductor, if he issued two tickets, as if he and "another" were together; and that this someone must have impressed the conductor if he looked at him a certain way, although Nicholas isn't quite sure of that. This state of doubt leaves room for a feeling of apprehension as he ventures into the subway tunnels, which had been defined some time before by his dead uncle, Douglas Lessing, "Halfway to Hell": it is as if the encounter with the supernatural creature, it was realized just when Nicholas enters and then ventures into the subway, a hellish way; and that same noise that terrifies him so much, that is, of knuckles and nails scraping the doors of the train as if trying to open them (don't the nails have demons?) ceases only when the train leaves for its final destination, and exits from underground. And when Nicholas hears a strange noise and perceives a strange smell? When the train enters another tunnel, another hellish corridor. The smell, which we can associate with a feeling of nauseating, sends us back to death: and it is a further step, to testify of what nature it is the being that follows it. Lessing will smell that sickening smell when he returns to his house, which was later that of his tycoon uncle. The same smell that in the third story will bind us to the olfactory sensation of moldy fur, that of the overcoat of the dead uncle. When he enters the house, he finds a double of him in a coffin. But in that figure so close to him, he finds the elements to disagree with that false truth proclaimed: the fellow soldier he had met in the war who looked like him like a drop of water.

Also in this second story, an important element that makes the story haunting is the noise of something dragged on the ground: a stick, which we had seen in the first story to be central. Here, the clothing is given by a shapeless overcoat and a grungy hat, almost as if it were a scarecrow. The greatcoat that was the black coat of the first story and the moldy fur coat of the last.

Why does the conductor talk about a blind being, and then the terrified passenger in the train adds to the dose, speaking of him as a very tall and blind figure? Not because you don't see, but because you wear glasses that let you glimpse that behind there are only two orbits you want: wasn't it death represented by a being with a skull face and wearing either a hooded robe or some ramshackle dress? Here in the orbits, when the being reveals itself to its brother, mad with fear, there are cobwebs, and from them yellow-black spiders fall. Death reveals what the task he is there for: she wants Stephen, she wants to take him with her. Stephen is a damned. He is alive, and he will be dead. And that he is damned, he fears it. Because? Because when Lessing walks into the room and crushes a big black spider that testifies that death has passed from there, his terrified brother begs him to reveal that that being is not the demon he thinks, but only an actor paid to have him fall into. mistake and betrayed himself. Because he fears meeting him again, in hell.

Once again, the noise of the stick brings the supernatural being back to the center of the problem: he has not gone away, he is leaving, but he will not go completely as long as Stephen is still alive. He leaves at dawn, because then Stephen dies. Not by chance at dawn, when the light comes out. Death returns in the darkness: a very tall figure is seen, carrying an old overcoat and a rickety hat under his arm, walking towards where? The subway, a road that according to old Douglas Lessing was the “Halfway to Hell”. When Stephen dies, that is, evil is defeated, and death returns to the Underworld, good triumphs: at that moment Nicholas embraces both Judith who had believed in him, and who as her aunt, did not. recognized. And the contrast that is typical of a Carrian supernatural story disappears: everyday life, opposed to an unreal reality, the Natural opposed to the Supernatural. That is, we return to a situation prior to the one in which the supernatural had peeped out.

But that it is a supernatural, fantastic story, the contrast that we read at the beginning of the story also testifies, when Nicholas Lessing recalls in the hushed rooms of his club, the Naughts-and-Crosses Club, how it all began: he introduces a reasonable doubt that everything has happened, when he mentions that everything manifested while he was tired from the journey, it was raining and it was night, all elements that contrast with the light of day, when we are rested and see things in the right light. But it is precisely the contrast between the hushed and safe life of the Club and the future of things that contrast with it, which produces the striking contrast that introduces Carr's supernatural stories. Doglas G. Greene, who introduces the stories, rightly states that the same places are where Carter Dickson will place the beginning of The Plague Court Murders. After all, it is that perception of something wrong, of astonishment, of doubt, which produces the fantastic, and which Todorov rationalized in his famous essay.

We note that in the three stories, respectively in that of 1927, in this one of 1935 and in that of 1939, the name of the protagonist is always different: in the first it is Wood Stoneman, in the second Nicholas Lessing, in the third Anthony Marvell, while a curious thing is the name of the villain, it is always the same: Stephen; only the relationship of kinship changes: in the first story he is a cousin, while in the second and third he is brother. The uncle also changes: in the first he is Stoneman, in the second he is Douglas Lessing, in the third he is the founder Jim Marvell. The other characters may or may not be there. It is obvious that the figure of the bad relative, in the second and third stories, is sharpened in wickedness: a brother who kills another brother for reasons of greed makes more impression than a cousin.

Together with the name that changes and that represents the dead uncle, the objects that represent him also change and that have a visual, olfactory and sound importance: the stick that makes a characteristic noise in the first story; the stick, which also makes noise, and the hat and coat in ramshackle as they appear in the second; the fur that smells of rotten, in the third.

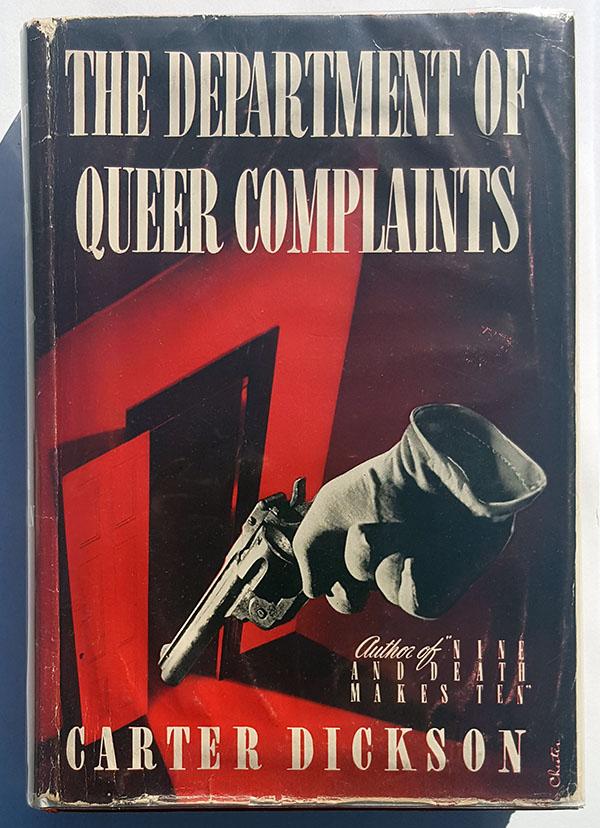

After having published the basic story changing its connotations and name in 1935, Carr took it up once again, adapting it this time for the magazine "Illustrated London News", on the occasion of Christmas 1939 and entitled it New Murders for Old ; however the story was reprinted on another occasion under the title The One Real Horror. The first edition, the English one, with the first title mentioned, New Murders for Old was then reprinted in the "Department of Queer Complaints" collection the following year, 1940.

SPOILERS

The story is that of the heir to a luxury hotel chain that went down the drain, founded by the old Jim Marvell. Inherited from his nephew Anthony, a young man devoted to a brilliant career as a mathematician and forced instead by the last will of his uncle who loved him, to take care of his hotels, instead of selling them and making as much as possible, as his brother Stephen, a surgeon, would have done. is applied to it, "mind and body" tirelessly, so that after two years of hard work and self-denial, risking nervous exhaustion, he manages not only to save them from failure but even to bring them to a sensational activity, to make them a destination for all the rich people who want a luxurious vacation.

But the setbacks are nervous in nature. And so despite him, he agrees to also give up the company of his girlfriend Judith Gates, a girl of humble origins, and to take a cruise that will keep him away from home for six months.

However, as soon as he embarked, his misadventures began: entering the cabin, he no longer found the baggage that he had left with his brother Stephen. Having reported the matter to the Purser, he hears the reply that it is he who gave the order just before unloading his luggage, directly, to the Purser himself. Tony doesn't know what to do and begins to doubt himself, his own mental clarity. He orders them to go get the bags, but then when he gets back into the cabin, he finds a pistol with bullets in the magazine on the mattress of the bed. He is increasingly confused, but instead of throwing it away from the porthole into the sea, he takes it with him. He even doubts that it is actually his. And he is increasingly convinced that he himself is the cause of his troubles: a conscious part of him is haunted by an unconscious one. Nothing happens once the ship has left port, except for one thing that makes him question his mental abilities: he has the impression on more than one occasion that old Uncle Jim is spying on him, tucked up in his old coat with an old-fashioned fur collar: the fact is that Jim Marvell is dead and gone.

After about six months of absence, perfectly recovered and feeling full of his mental faculties, he decides to return home. But here in the train that is taking him back, in his compartment he finds a newspaper of the day before that talks about his death by suicide. Recovering from his surprise, he apprehensively discovers that it cannot be a fake: the article is too detailed, the people are those of his family, the places are those of his ancestral home. Tony doesn't know what to fish for, he even begins to doubt he's Tony Marvell. Meanwhile, there is someone on the train who does not lose sight of him, a person with an old-fashioned fur collar.

Tony tries to get into the cab, and here the guy is behind him. It's snowing. The taxi would arrive at its destination and above all he would be able to sow that unwanted visitor once and for all, but the taxi has an accident having had to avoid at the last moment a man covered by a heavy coat with a fur collar.

Tony gets out of the car and lo and behold, his unwanted companion is behind him. He accelerates the pace and the same. Tony runs, but also the one behind him. Tony has the house keys, he is about to open the door but they escape him. When he succeeds, that vaguely familiar figure is behind him. Seized by terror he tries to react by trying to grab the gun but it falls. He takes refuge upstairs and enters his room. He turns on the lights and notices that someone is lying in his bed, covered by a sheet. He conquers fear, discovers the sheet and finds himself another Tony Marvell.

Shocked, he turns and sees his brother Stephen talking to him but while this happens, the figure that haunted him is there. Stephen screams, screams, one hand, that of being locks Tony in his room in the company of his double, and then, after another cry for help from Stephen, after the housekeeper has rushed in time to see the door of Stephen's room close, here is a gunshot: Stephen is found killed with a gunshot to the head.

And the killer? Volatilized: the windows were bolted. No one was present inside when they opened the door, and outside was the housekeeper who swears that no one, absolutely no one has entered. To testify that there might be someone there, just a faint smell of moldy fur.

The story ends as it began: the CID superintendent told Tony's story to his girlfriend Judith. Tony is free from any suspicion and he owes it above all to the fact that he has been locked in his room. Stephen is dead. Suicide, is the final verdict. No one was in that room and no one could have left it. But why would he ever kill himself? And who was Tony's double? But was he really Tony, Tony Marvell?

THE END OF SPOILERS

Of the three versions of the same story, the second is the longest and the most terrifying: it is normal for Carr to amend the most terrifying passages, for a re-edition with another title, for a Christmas edition.

Already in the first lines you begin to sense the horror of the story: Sir Heargraves, Superintendent of the CID, is telling a story to another person and they are in a room: the identity of the person is unknown and will be revealed only at the end, because if it were revealed immediately, it would remove some suspense from the story. Plus Sir Hargraves alludes to a "thing" that was there on the bed. Mind you: he is talking about a "thing". Then Carr writes that the air had a faintly sweet smell. Sweetish! When this meaning is used in a detective novel, a mystery, the reference is always to the decomposition of a body: putrefaction gives rise to nauseating and sweetish scents.

The way in which Carr introduces the story already has the touch of genius in it: it's cold and snowing outside, but inside the atmosphere is suffocating, and there is still a touch of sweetness. When he talks about something about the bed, it reminds me of a Talbot novel. Surely this calling the body on the bed "what" is a direct reference to that other "thing", on the bed of another bedroom, in The Hangman's Handyman.

Hake Talbot's novel is from 1942. Talbot and Carr were friends: it is well known. At least it seems strange to me, and I underline it, that characters appearing in Talbot's novel are present in this story which is earlier.

What Do I mean? That it could also be that Talbot took things from Carr, from this Carr, despite the fact that he had claimed that his main inspiration was the Melville Davisson Post of the stories of Uncle Abner: both texts speak of an impossible murder, in in both cases a supernatural situation enters into it (only that in Carr it could be true, in Talbot it is shown that it was not in reality), in both cases there is a double that is a double (in Carr's story it is true, in the novel of Talbot no), in both cases there is recourse to the theme of the putrefaction of bodies post mortem (in Talbot it is the cause of the problem: a curse aimed at making a body rot in a short time; in Carr the effect: the double killed himself a few days earlier); in both cases we speak of a "thing" lying on the bed and covered by the sheet (in Carr we speak of thing, a term also used by Talbot; Talbot adds that it looked like a "slug").

Also this time, the previous story of Le Fanu has its fundamental importance, just as Jim Marvell is also here The Man of Stone from the first story. If in Carr's tale, the narrow marking of the mysterious figure in an old-fashioned fur-collared coat would seem to be an omen, or at least an expression of an evil power (and the connection to Le Fanu is glaring), Carr revolutionizes the whole, because if Tony fears that stalking because he thinks he wants to somehow make an attempt on his life, in reality the figure just wants to save him. Uncle Jim loved him and therefore would not have wanted him dead even when he was dead. Instead, it is as if his suffocating presence were the only move to guarantee Tony to stay alive: in fact, he was already the victim, not knowing it, of an unsuccessful attempt at "perfect crime" only because an unsuitable killer was chosen. to the role because unable to kill.

It would have been a perfect murder if Tony Marvell had disappeared after getting on the ship, and another Tony Marvell exactly like him had materialized in his place, as it would have been a perfect crime if "The Iron Mask" had replaced him. Louis XIV, condemning him in his place to an ancestral imprisonment in the Bastille). And the connection to the second story is immediate if we think of the double in charge of replacing him at his home. Instead Stephen's perfect murder if you don't believe the suicide theory (why would he scream and why would he lock Tony's bedroom door from the outside, why surely the housekeeper didn't? ), it certainly is, but accomplished by a living dead, by his uncle who woke up from eternal sleep.

Just Roberto Sonaglia (translator of the story into Italian), gives me the opportunity to underline another character of this story that resides not only in its having a supernatural double ending, but also in being a Gothic story. In this regard, Sonaglia wrote an article on the Gothic in Carr, published - as an appendix to G.M. 1821 of 1983, in which the unpublished Carr He Wouldn't Kill Patience was published - together with two articles by Boncompagni and one by Lippi. Here is a short extract that also applies to the story in question:

“Carr does even more; proposing a particular dimension of the mysterious, developed at the time by Gaston Leroux, he even plays on the existence / nonexistence of the supernatural, an artifice much more suited to our shrewd minds that ideally smile at ghosts and, however, do not yet know whether to believe or less to a metaphysical reality. This elegant game, as in the neo-gothic, presents all the symptoms of an aesthetic taste biophile, retracing the path traced by the classic ghost story where the spirit, with its incorporeality, already moves the index from the carnal to the impalpable, from the horror to the mystery."

Roberto Sonaglia thought is clearly acceptable, and it is applicable - also for what I have said - when for example it insinuates that the figure hiding behind a plant on the ocean liner, is the old Jim Marvel, or rather his ghost, indicated by one detail, the old-fashioned fur collar of the coat old Jim used; or when this figure insinuates that he is present on the train, that he follows Tony to the taxi that will take him home, that she is the one that makes the taxi skid so that Tony arrives home not immediately so that he, the undead can tail him , steal the gun and then kill.

However, the story in addition to the gothic and supernatural characters that can happen are complementary (for example the old austere, dark house, with noises and creaks, and a ghost or in any case a living dead, are two clearly combinable subjects), also has the fantastic one. In fact, the way as it leaves the reader, alternatively viable, the path of the impossible murder carried out by a being who enters the room and then literally vanishes there without a trace or that of suicide just as unlikely knowing the victim (traceable for example in the two other stories cited and in the novel The Burning Court), causes the reader to be interested in the kind of estrangement Todorov talks about in his essay on the fantastic.

Reflecting at this point on all three stories, it can be said that the first tells the bare facts, while the second and third enrich it with the impossibility that was not foreseen in the one of 1937. In addition, the second and third, markedly underline the supernatural character of the story, and enrich it with elements not present if not hidden in the first: eg. the tension. In the second and third, but especially in the second, the tension is increased to spasmodic levels in the subway, in dark and not crowded places, where tension is the consequence of the fear of being reached by something that is not known, and that wants at all costs reach you. It is therefore a tension created by also resorting to psychological expedients. Furthermore, Carr creates here a story that has many points of contact with Horror, and if you see well, beyond the editorial destination of the second story, the first already possesses these stylistic features, which he shares with many other works, contained in The Hafervordian and also in some novels with Bencolin, such as It Walks By Night, Castle Skull and The Waxworks Murder (aka The Corpse in the Waxworks).

Finally, the second and third versions of the story are much more justicialist than the first version, as they focus on the condemnation that is not only human but also and above all otherworldly of the offender, who when he is killed by the supernatural creature or kills himself , it is as if he is forever condemned to damnation.

PIETRO DE PALMA