"Reader Beware: SPOILERS"

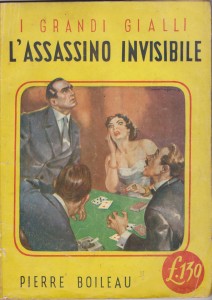

Pierre Boileau, before he met Thomas Narcejac, wrote

eight novels that gave him fame, and among them, too, "L' ASSASSIN VIENT

LES MAINS VIDES" (1945).

Like other novels of Boileau, this begins without an introduction: Brunel and his companion, Pierre, who narrates the story, as usual, on the street, are almost run over by a former comrade of Pierre who then greets them warmly and invited them to best coffee on the Champs Elysees, where he will make know to the two cousin, Alex Fontaille. He, grandson of a landowner, Apolline Fontaille, who has grown up as a child, joined romantically with a note dancer of Parisian nightclubs, Monique Clerc. From the first moment, he doesn’t prove to be serene and yet insists that the two friends of his cousin, go with him to the estate of her aunt, Les Chaumes.

While they are in Paris, Brunel realizes that someone is keeping an eye on, and later recognize in this the personal home of the old Apollo, Simon.

The old, newly arrived, mistreats the other nephew, Georges, guilty of not having visited her in recent times, and welcomes newcomers with a lot of fuss.

Like other novels of Boileau, this begins without an introduction: Brunel and his companion, Pierre, who narrates the story, as usual, on the street, are almost run over by a former comrade of Pierre who then greets them warmly and invited them to best coffee on the Champs Elysees, where he will make know to the two cousin, Alex Fontaille. He, grandson of a landowner, Apolline Fontaille, who has grown up as a child, joined romantically with a note dancer of Parisian nightclubs, Monique Clerc. From the first moment, he doesn’t prove to be serene and yet insists that the two friends of his cousin, go with him to the estate of her aunt, Les Chaumes.

While they are in Paris, Brunel realizes that someone is keeping an eye on, and later recognize in this the personal home of the old Apollo, Simon.

The old, newly arrived, mistreats the other nephew, Georges, guilty of not having visited her in recent times, and welcomes newcomers with a lot of fuss.

Had the rooms,

after dinner, Brunel, Pierre, Alex and his girlfriend, they decide to play

bridge, after they smoked and drank, while Georges walks around outside in the

garden. The

old asks Alex to go to make an inspection and to close everything, that Alex

does, and then returns by fellow: but while they are playing, they hear the

loud voice, coming from the first floor, the room of the old: find her stabbed, in a pool of blood. While

Alex is to watch over the corpse of her aunt, Brunel and Pierre share the

tasks: each goes up and other goes down. Pierre determines that if anyone had

entered from the out

in the house, he would be in front of Gustave, who was putting in place the

crockery and cutlery used for dinner, so the murderer may be gone just above

the second floor, where there are none. From

the second floor, dropped only Simon, the domestic staff of Apolline Fontaille,

trustworthy, with bare feet in slippers and robe bedroom tucked haphazardly in

the pants: unless both he and the murderer, this must have

disappeared: in fact, even if the window was open, being summer, the assailant

could not have fallen, because on ivy that clings on the outside walls, you do

not notice anything that might indicate that hypothesis. The murderer, if he’s

not Simon, has “vanished into thin air”. But why Simon would kill the

old woman? He

had no reason to do it, the more he perceived a very high salary, not

commensurate with his duties: if at first you suspect blackmail, then learns

that Simon was very dear to the old woman who had raised him since he was

little ,

saving him from the clutches of unnatural parents who beat us mercilessly even

at an early age, and he had always countered with dedication and affection the

care of his mistress. So

Simon is ruled out, but then where is the murderer? And what Simon was doing in Paris?

It’s

clear, however, that he must know something he doesn’t intend say, that can be put in

connection with the murder of the old woman.

From examination of the body of the old woman,

who is undoubtedly dead, we discover two very close wounds, signs of two stabs:

the weapon is a sharp letter opener, found near the bedspread, with a handle

inlaid, as to eliminate the possibility on it may be fingerprints.

While waiting for the next day the cops arrive, Pierre will watch, alternating with Brunel, the corpse of the old woman, in her room. But, Pierre falls asleep; at some point, however, he wakes, sweating from the tension, because he realizes that in the darkness of the room, there is someone else that moves: he would like to do something but does not have weapons and then thinks about what to do, while the other is taking the cards, which he hears the rustle of. Suddenly, he remembers the electric bell that the old woman had wanted in her room, to call Simon: he presses several times it, and shortly after he hears someone knocking at the door. After his invitation to come in, the light switch is pressed, the light shines in the room: Simon is on the door. But besides him, Pierre, in the room there is only the corpse of the old: unless it is a vampire, this time too the mysterious visitor has vanished.

Possible that is there a secret passage? Impossible. All deny it there is. So? How did the visitor to vanish? Brunel is doubtful, but Pierre insists. He also heard a rustle and a characteristic noise, like something that had been opened. Brunel has an epiphany: the secretaire. Open it, and there, from a drawer, see out a card: it is a holograph testament replacing another precedent: in it Georges Durbans is appointed sole heir. At this point, if you ever brought a growing possibility that he was the murderer (the rest he was in the garden, was the only one of the group, were not together at Brunel and Pierre) now he becomes more real, although Georges seems anything but a murderess. The strange thing is that the old woman had before prepared another testament that appointed Alex her heir: why that testament, then? Brunel curses for not having examined immediately after the discovery of the corpse, the secretaire, because now is the double possibility: it is a testament true or false? Why did the visitor open the bureau? The testament, penned with calligraphy seems shaky, as if the hand that had thrown down was not entirely sure: the old or the murderer who has imitated the handwriting?

While waiting for the next day the cops arrive, Pierre will watch, alternating with Brunel, the corpse of the old woman, in her room. But, Pierre falls asleep; at some point, however, he wakes, sweating from the tension, because he realizes that in the darkness of the room, there is someone else that moves: he would like to do something but does not have weapons and then thinks about what to do, while the other is taking the cards, which he hears the rustle of. Suddenly, he remembers the electric bell that the old woman had wanted in her room, to call Simon: he presses several times it, and shortly after he hears someone knocking at the door. After his invitation to come in, the light switch is pressed, the light shines in the room: Simon is on the door. But besides him, Pierre, in the room there is only the corpse of the old: unless it is a vampire, this time too the mysterious visitor has vanished.

Possible that is there a secret passage? Impossible. All deny it there is. So? How did the visitor to vanish? Brunel is doubtful, but Pierre insists. He also heard a rustle and a characteristic noise, like something that had been opened. Brunel has an epiphany: the secretaire. Open it, and there, from a drawer, see out a card: it is a holograph testament replacing another precedent: in it Georges Durbans is appointed sole heir. At this point, if you ever brought a growing possibility that he was the murderer (the rest he was in the garden, was the only one of the group, were not together at Brunel and Pierre) now he becomes more real, although Georges seems anything but a murderess. The strange thing is that the old woman had before prepared another testament that appointed Alex her heir: why that testament, then? Brunel curses for not having examined immediately after the discovery of the corpse, the secretaire, because now is the double possibility: it is a testament true or false? Why did the visitor open the bureau? The testament, penned with calligraphy seems shaky, as if the hand that had thrown down was not entirely sure: the old or the murderer who has imitated the handwriting?

Not even the

handwriting expert appointed the next day to make a judgment, will lean much:

the testament would seem to be from old woman, but then he is not entirely

sure.

While you can not get away from a spider hole by the woman's death, and Brunel concerns that something else could happen, here's a second murder, to disturb the atmosphere: Alex is killed, he also stabbed in the heart with a letter opener, very similar to the first. Pierre sees a shadow that falls from the window, he throws himself on him, but that man avoids him, instead of killing him too: why did he risk being taken, if he killed a man before, and now he did not want to attack Pierre instead?

Brunel investigates and discovers that shadow was someone who had met with Alex, who was the first husband of Monique, a gentleman. If he was not he killer of Alex, who did kill him? Simon, Monique, Gustave, Brigitte, or Georges? Since it wasn’t possible that the force required to launch the stab was from a woman, suspects are three men: Gustave, Simon or Georges?

While you can not get away from a spider hole by the woman's death, and Brunel concerns that something else could happen, here's a second murder, to disturb the atmosphere: Alex is killed, he also stabbed in the heart with a letter opener, very similar to the first. Pierre sees a shadow that falls from the window, he throws himself on him, but that man avoids him, instead of killing him too: why did he risk being taken, if he killed a man before, and now he did not want to attack Pierre instead?

Brunel investigates and discovers that shadow was someone who had met with Alex, who was the first husband of Monique, a gentleman. If he was not he killer of Alex, who did kill him? Simon, Monique, Gustave, Brigitte, or Georges? Since it wasn’t possible that the force required to launch the stab was from a woman, suspects are three men: Gustave, Simon or Georges?

Moreover,

Alex, before being found dead, he had closed twice the door and about this

Pierre was sure, because he had distinctly heard the two shots: but then, after

the discovery of the corpse of Alex, they found the door house

no longer closed: it means that there is an accomplice as well as a murderer,

who apparently does not know that the murderer escaped from the window, because

obviously the plan assumed that he had to escape through the same exit, so

surely will

have to go back down to close the door and prevent you might think about him as

an accomplice, unless he is not Simon, who as butler, also has the task of

asking and open the door in the morning. They

will agree to watch over the door so as to catch the accomplice or not, in

which case it would be true the other hypothesis. No one will come down. Brunel,

after a sleepless night, will be able to name the killer and to solve the

riddle, discovering how the robe of the woman had not two but a single cut,

which is not properly screened in the reconstruction of the crime. And

he will be able also to fulfill from the charge of complicity in the murder of Alex,

Simon.

Novel highly enjoyable, it is based on an Impossible Murder and on a Locked Room, which a thief was able to evaporate from.

At the base of the riddle is the result of reasoning by Brunel: "the facts are presented as well: the murderer comes to his enemies ... without knowing exactly what he will do, and these terribly afraid that visit, but without power to predict how it will play . One does not have weapons to kill, others do not have weapons to defend themselves". In fact, twice the murderer has used something that was in the house, and then, it was not premeditated he killed, otherwise he would have brought a weapon. Yet he must have an accomplice, to premeditate to go into the home.Why?

At the base of the riddle is the result of reasoning by Brunel: "the facts are presented as well: the murderer comes to his enemies ... without knowing exactly what he will do, and these terribly afraid that visit, but without power to predict how it will play . One does not have weapons to kill, others do not have weapons to defend themselves". In fact, twice the murderer has used something that was in the house, and then, it was not premeditated he killed, otherwise he would have brought a weapon. Yet he must have an accomplice, to premeditate to go into the home.Why?

Boileau, as at

other times, he climbs on the mirrors: he demonstrates an unmatched virtuosity

(equaled only by Vindry and Lanteaume), in proposing a problem and its

solution, when he has few ingredients, which, moreover, is a bit the typicality

of

French novels of the period: insist on the mystery, propose one or more problems,

attractive enough, without however enlarge the rose of suspicion, because not from

the juxtaposition of alibis and motives must exit the solution, but from the

proposition of the problem in itself, because in essence it is based on the plot and its variations . In

addition two other differences with the Anglo-Saxon novel occur: first there isn’t

a real introduction, in which matures the crime, that is a typical feature of

British detective novel instead (but not the US); and

then, as a result, the French detective novel, and particularly that by

Boileau, bases its plot on something that is done randomly, without that the

reader has already seen or knows or at least images why a particular crime is

consumed: it is a novel, we might say, police-type-adventurous, heir of the

atmosphere from feuelliton, a dramatized feuelliton, by Leroux and Leblanc; second

difference, I would say, is inherent in the fact that, while the British

detective story, just to be different from that of the appendix, where if there

was a crime, you had to look for the woman and the butler, tends to present

among suspected all

the characters with the possible exclusion of the domestics (and this

essentially for a social classism, almost racist, presenting the domestics a

step lower than the nobility or the upper class, the only one that could

consume a perfect crime, which for

intelligence can not belong to a lower social order), in the French detective

novel, as a consequence of the fact that domestic, bosses, police,

investigating judges, all as part of their duties are citizens of the republic,

even the servants are to be suspected like

the masters.

This broadens

the rose of the suspects, that, as we reported earlier, it is always quite

small. This

of course would lead to a job easier for detectives, and then there is the need

to turn and re- turn over the tangle, not only to lengthen the stock (in fact

the French novels of the time are not as long as those English) but

also not to attenuate the narrative tension which otherwise would weaken

naturally.

In the case of this novel, the specific character and insist on the topics that we have just pointed out, reveal a very subtle reasoning, a true virtuosity of the deduction and of the sophistry, I would say by Byzantine kind: able to turn the problem, giving of each problem two or more possible solutions, from which we have many different solutions, which mainly concern here from: the will, true or false (it could be that the murderer had created a fake to create a perfect culprit, ie Georges; orit is false because posted by Georges, or is true, and then it was inserted long before by the old Fontaille); the thief invisible: how did he disappear; the problem of the lock of the front door and two turns, and about a possible accomplice; the problem of the existence of two wounds and that the robe presents a single cut; how did disappear the murderer; why Alex did try to defend himself with a piece of wood taken from the fireplace (this was found clutched in his hand); why there is not an accomplice; what the murderer or the thief took from the secretaire.

In the case of this novel, the specific character and insist on the topics that we have just pointed out, reveal a very subtle reasoning, a true virtuosity of the deduction and of the sophistry, I would say by Byzantine kind: able to turn the problem, giving of each problem two or more possible solutions, from which we have many different solutions, which mainly concern here from: the will, true or false (it could be that the murderer had created a fake to create a perfect culprit, ie Georges; orit is false because posted by Georges, or is true, and then it was inserted long before by the old Fontaille); the thief invisible: how did he disappear; the problem of the lock of the front door and two turns, and about a possible accomplice; the problem of the existence of two wounds and that the robe presents a single cut; how did disappear the murderer; why Alex did try to defend himself with a piece of wood taken from the fireplace (this was found clutched in his hand); why there is not an accomplice; what the murderer or the thief took from the secretaire.

Doing so, Boileau

manages to keep the tension very high, and if so far the reader has had a few

suspicions and then essentially was taken to concentrate his attention on very

few, because two, Alex and Monique are kept out from their own investigations because

they played, together to Brunel and Pierre, bridge (a game that often appears in the

novels of the time, by De Angelis to Agatha Christie, Dorothy Sayers to

Stanislas-André Steeman), precisely during the solution, in which the suspence should

cathartically fall,

in this by Boileau, instead, it increases spasmodically because in a totally

unexpected final, happens everything and its opposite. And

everything is explained, as a murderer and a thief, different people, can

vanish in an enclosed area without being detected, and as a murder in which

there can not be an accomplice, he lacks; and

finally as Simon, although not murderer,

let alone the killer's accomplice in the murder of Alex, he is in a sense an

accomplice of another murderer, that of the old woman, although he can not in

any way be involved in the murder of her.

Extraordinary!

Boileau really he is, because, and this is the biggest surprise, far from creating a novel based exclusively on clues, just in solution reveals a mechanism very cerebral, with a very pronounced psychological aspect, which concerns the way of shuffling the cards and turn the reader's attention, creating the conditions because, on the basis of acts very obvious, he is led to believe one thing instead of think of another. To give a measure of the mechanism of the highest stylistic virtuosity, I emphasize two particular moments which for me are the measure of true creativity and power of reasoning by Boileau: the closing the front door, and the volatilization of the thief after Simon knocked three times on the door of the room where is the corpse by Mrs. Apolline, watched over by Pierre. It is the mechanism of sound illusion, explained in a famous story by Clayton Rawson, From Another World, about which I wrote an article that I have not yet translated into English, in which I wrote that for the first time I had read about a sound illusion, and this had left me speechless. I was wrong. I thought that this was the first time that had been used such an illusion, and instead already three years before a French had used it: Pierre Boileau.

This novel reveals a pattern common with another novel, Six Crimes Sans Assassin, for the way in which the murderer leaves the scene. In this, and we also noticed in the case of La Promenade de minuit and Six Crimes Sans Assassin, Pierre Boileau tends to reuse in later novels, gimmicks and escamotages that he has already used his other previous.

Boileau really he is, because, and this is the biggest surprise, far from creating a novel based exclusively on clues, just in solution reveals a mechanism very cerebral, with a very pronounced psychological aspect, which concerns the way of shuffling the cards and turn the reader's attention, creating the conditions because, on the basis of acts very obvious, he is led to believe one thing instead of think of another. To give a measure of the mechanism of the highest stylistic virtuosity, I emphasize two particular moments which for me are the measure of true creativity and power of reasoning by Boileau: the closing the front door, and the volatilization of the thief after Simon knocked three times on the door of the room where is the corpse by Mrs. Apolline, watched over by Pierre. It is the mechanism of sound illusion, explained in a famous story by Clayton Rawson, From Another World, about which I wrote an article that I have not yet translated into English, in which I wrote that for the first time I had read about a sound illusion, and this had left me speechless. I was wrong. I thought that this was the first time that had been used such an illusion, and instead already three years before a French had used it: Pierre Boileau.

This novel reveals a pattern common with another novel, Six Crimes Sans Assassin, for the way in which the murderer leaves the scene. In this, and we also noticed in the case of La Promenade de minuit and Six Crimes Sans Assassin, Pierre Boileau tends to reuse in later novels, gimmicks and escamotages that he has already used his other previous.

A very magnificent novel!

Pietro De Palma